|

|

SEPTEMBER 1997 CONTENTS

|

|

ALUMNI NOTES

|

|

ALUMNI NEWS

|

|

ALUMNI SCRAPBOOK: SPRING REUNION

|

|

HANDOVER IN HONG KONG

|

|

GET IN TOUCH

|

|

I have come to Hong Kong to witness

what is referred to as "the Chinese take away," a spoof on

what we call carryout here. Amid the hype, I search for the

unfolding of smaller moments. Former British Governor of

Hong Kong Christopher Patten has said that "history is what

comes before and after the dates we all remember." If his

sentiment is accurate, then perhaps my observations during

the few days leading up to the handover on July 1 can

provide a glimpse of history.

|

Handover in Hong Kong

By Jean Grisgsby (MA '94)

On our first day of touring, we must take the bus to the ferry to the bus. A crowd waits at the stop, and once the bus arrives, everyone rushes the door. Teenagers jostle grandmothers, businessmen shove mothers with young children. The friends we are staying with, who have lived here for two years, describe Hong Kong's residents as "the worst of the East meets the worst of the West." As we ride along, a cellular phone rings. A man answers, and begins a loud one-sided conversation.

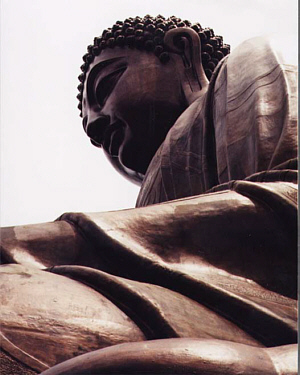

We are exploring Lantau, the largest of the outlying islands, and head for the Po Lin Monastery, where the "Big Buddha" resides. We first spy the 112-foot-high Buddha, the world's largest outdoor statue, in the distance, as the bus winds along the mountainous island roads.

We have heard that there are one million visitors in town for the handover, and so it comes as no surprise that our initial encounter with the Buddha is less than spiritual. There are camcorders, cameras, and tourists everywhere. It is almost impossible to take a photograph without getting in someone else's shot or having them become part of yours.

This pilgrimage is more like a trip to Graceland than anything else; its oddball attraction is what is strangely awe-inspiring. Fortunately, this Buddha, while large (about 275 tons), is not of the fat, laughing variety. He sits serenely, eyes closed, right hand raised with palm facing outward. Ultimately, its size and countenance, if you can work in a quiet moment, are arresting.

Our ticket to the Buddha also buys us vegetarian lunch en masse at the monastery. Once inside the canteen, we are guided to our seats at a large table. We join an older Chinese couple, who speak no English but are happy to serve as hosts by sliding the huge bowls of rice and broth toward us. Soon others arrive at our table: a couple from Mauritius and a father and son.

The son, we learn, is from Hong Kong, but now lives in Singapore, where the cost of living is not so painfully high. He boasts about the spacious apartment he is able to afford there. He is happy about the handover and does not think it will affect the economic climate in the future.

Unlike Hong Kong Island, Lantau has vast and beautiful green spaces. More than 50 percent of the island has remained undeveloped and is extremely well-maintained parkland. Thousands and thousands of stones, for example, have been placed as steps on the steep trail up to Lantau Peak.

If the Big Buddha is Graceland, then Lantau Peak is the Grand Canyon. The view from the top is one of the most spectacular in the world. When the weather is clear, it is possible to see all the way to Macau. From here, the Buddha appears as small as one of the ubiquitous tabletop versions sold in souvenir shops, and to the north, we can see the new airport being built on Chek Lap Kok Island. The airport is but one of many "reclamation" projects; mountain tops are removed and used as fill to create more land for more buildings. What's left are flattened, smaller islands like so many brown tree stumps in the South China Sea.

Sunday, June 29

We head north to Lok Ma Chau in the New Territories, near the Chinese border. We have heard that the People's Liberation Army will march through this area, and we want to scout locations for possible troop watching on the 30th. The border crossing is like any other in the world--there are barbed wire fences, dogs, guards, and lots of idling trucks. The air is so full of diesel fumes that our eyes sting and our lungs are choked.

We turn off the paved road, cut across a field, and enter a village, really only a cluster of joined houses, as well as a temple and a school with a courtyard that have been spruced up and decorated with Chinese flags and banners. Several Chinese men emerge from the school and surprise us by offering greetings in nearly perfect English.

They are father and son, leaders of a clan recently returned from Britain -- "Nottingham," explains the son, and "Piccadilly," the father adds. As it happened, the entire clan emigrated for economic reasons more than 30 years ago--and found financial success in the restaurant business. The clean, orderly buildings and the decorations we see now are their handiwork. The clan has come back in enthusiastic anticipation of Chinese rule and is busily preparing for a family blowout. "Our family has owned this land for thousands of years," explains the son. "We will keep our restaurants [in Britian] and travel back and forth to run them. But we are happy to be here and part of China again."

We decide to take the train across the border into China and spend the night in Shenzhen. We get our first inkling of the joys of dealing with the Chinese authorities, when we are assessed $HK100. We ask the Chinese guard why we have to pay when our guidebook makes no mention of a fee, and he tells us that only tour groups are absolved from paying the fee. As we press the guard further, a young man who looks like he might be from India leans over and whispers some friendly advice: "You really don't want to make them mad." With that, we decide to cut our losses and move on.

Shenzhen, one of six special economic zones in China, is not at all like the quaint village I had imagined. Shenzhen is L.A. on a smaller scale--flashy and hip and loud--with hotels, nightclubs, and streetwalkers. And tonight, the mood is jubilant. Red paper lanterns and Chinese flags hang everywhere. Restaurants are noisy and full; sidewalks are crowded; and the outdoor market stays open well past midnight. Doormen, shopkeepers, and waitresses trip over one another to serve us. Workmen scurry to assemble colorful arrangements of potted flowers, while a guard stands watch over their work.

The People's Liberation Army has already arrived, and none of the rooms on the south side of our hotel have been rented out, because Jiang Zemin's procession will be passing through on its way into Hong Kong.

Monday, June 30

In the evening, the festivities begin in earnest, and my feelings are complex. I watch the Brits crying on the TV news and understand their sadness, but as an American anticipating my country's celebration of independence from Britain, I am happy for the citizens of Hong Kong. Yet, I feel far more anxious about the handover than they seem to. Their nationalistic pride appears to outweigh any apprehension about the future. At least for the time being.

Bands play, guns salute, soldiers march, speeches are made. In Statue Square, where democratic party members are demonstrating, there is a strange kind of energy--brought about by a crowd comprised of demonstrators-in-earnest, international journalists, and merry-making tourists. To the tourists, this is Carnival or New Year's Eve, an excuse for banner waving and public drunkenness. The demonstrators pass out de rigueur fliers and chant. But if they represent the popular view, why are the demonstrators outnumbered two-to-one by journalists?

At midnight, Victoria Harbor is full of patrol boats with flashing blue, red, and green lights, as the HMS Britannia sails away. Rather than signing off for the last time, BBC radio will be broadcast from the ship until the signal fades out of range. Very soon the Chinese, the "new owners," will arrive. The People's Liberation Army has already massed at the border (ahead of the agreed-upon time) and will travel to Hong Kong in troop carriers and buses, filled with soldiers sitting at attention.

I suppose the most valuable lesson we can take away from the take away is that grand events and history often fall at opposite ends of the spectrum. And that, unlike such events, much of what is ultimately most historic is gradual and frequently goes unnoticed.

The restauranteurs we met near Lok Ma Chau expressed confidence that they would be free to come and go, free to run their businesses in Britain. "We're Chinese," they told me. But so were the students at Tiananmen Square.

Rumor has it that reclamation will continue unchecked and in time all the land on Lantau will be consumed by development. Meanwhile, plans are under way for two Chinese bank branches at the new airport. The British Bank of Hong Kong, the largest bank in the world, will have only an ATM machine.

Jean Grigsby (MA'94) is a freelance writer living in Baltimore.

RETURN TO SEPTEMBER 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS.