News Release

|

Office of News and Information 212 Whitehead Hall / 3400 N. Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-2692 Phone: (410) 516-7160 / Fax (410) 516-5251 |

November 12, 1996 For Immediate Release CONTACT: Phil Sneiderman prs@jhu.edu |

Power from Plastics:

Hopkins Scientists Create

All-polymer Battery

Researchers at The Johns Hopkins University have developed an

all-plastic battery, using polymers in place of the conventional

electrode materials. The battery, which is rechargeable and

environmentally friendly, has military and space applications and

may soon be suitable for small consumer devices, such as hearing

aids and wristwatches.

Researchers at The Johns Hopkins University have developed an

all-plastic battery, using polymers in place of the conventional

electrode materials. The battery, which is rechargeable and

environmentally friendly, has military and space applications and

may soon be suitable for small consumer devices, such as hearing

aids and wristwatches.Popular Science magazine honored the battery today with a "Best of What's New" award, naming it one of the top 100 new products, technology developments and scientific achievements of 1996.

The Hopkins project was initiated and funded by Rome Laboratory, a U.S. Air Force research and development center in upstate New York. Air Force officials asked Hopkins to create lightweight plastic batteries that could be molded into almost any size and shape for use in satellites and important military equipment.

Supervising the research at Hopkins were materials science and engineering professors Theodore O. Poehler and Peter C. Searson. Along with researchers Jeffrey Killian, Hari Sarker and Jossef Gofer, they have produced polymers that can generate up to 2.5 volts in cells that potentially could compete with the 3-volt lithium batteries now on the market. As part of this collaborative effort, engineers at Hopkins' Applied Physics Laboratory, led by Joseph Suter, have been paving the way for practical systems applications by linking the batteries with an innovative solar cell charging system. They also have contributed important technology and fabrication know-how to the project.

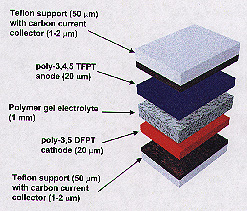

Building an all-plastic cell was difficult because most polymers that conduct electricity lack sufficient energy difference to serve as electrodes. Batteries consist of three main components: an anode (the positive electrode), a cathode (the negative one), and an electrolyte (the conductive material between the electrodes, such as the liquid in a car battery). Although other researchers have used a polymer for one of these components, Hopkins scientists are among the first to create a practical battery in which both of the electrodes and the electrolyte are made of polymers.

Lab tests indicate that the Hopkins cells can be recharged and reused hundreds of times without degradation. Yet unlike nickel- cadmium rechargeables, the all-polymer batteries contain no heavy metals, which can contaminate soil and water. The polymer batteries also contain no liquids, which can leak and pose safety hazards.

The all-plastic battery operates efficiently in extreme heat or cold. "A lot of battery materials vary with temperature," said Poehler, who spearheaded the five-year research project. "For example, your car battery doesn't start well when it's cold. But you can cool the polymer battery much colder than you're ever going to cool your car, and its properties don't change."

In addition, this power cell's unusual thin sandwich design makes it highly adaptable. The anode and cathode are made of thin, foil-like plastic sheets. The electrolyte is a polymer gel film placed between the electrodes, holding the battery together. The cell can be as thin as a business card, although a more power- intensive application would require a larger unit. This thin, flat design could allow battery users to cut a cell to fit a specific space. "You can make it into whatever configuration you want," said Searson. "You can imagine using it in a large sheet form, so that you could have a battery that occupied an entire wall, for example, but had very little thickness. Or you could roll it up into a tube, like AA-size batteries."

These characteristics may be particularly useful in space satellites, where polymer battery sheets could be slipped into crevices without adding much extra weight, the researchers say. If they were connected to solar cells, they could be recharged by the sun's rays while the satellite is in orbit.

In recent months, the Hopkins researchers have applied for patents and Fielded dozens of inquiries from battery manufacturers who are considering mass production of the all- polymer cells. "These batteries are very easy to make, and they use simple stuff--organic compounds," Poehler said. "It's no more complicated than what they're making now. The process is simple. I don't see why they would cost any more money to make."

|

Johns Hopkins University news releases can be found on the

World Wide Web at

http://www.jhu.edu/news_info/news/ Information on automatic e-mail delivery of science and medical news releases is available at the same address.

|

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page

Go to

Headlines@HopkinsHome Page