|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Living Well

The ElderPlus program at Hopkins Bayview provides aging Baltimoreans with all-inclusive healthcare aimed at keeping them out of the emergency room and the nursing home.

By Maria

Blackburn |

|

| Opening photo: Inez Scott receives a hug from Hopkins ElderPlus patient aide Audriene Johnson during breakfast. |

Inez Scott has spent many of the last 84 years doing for

herself and her family. She's raised three children, is

grandmother to five, great-grandmother to four. She worked

full time for state government for 27 years and volunteered

at church for 50. Every spring Scott planted her garden

with string beans, potatoes, and beets; every fall, she

picked, canned, and froze her harvest herself. Scott was healthy, strong, and independent. Then at the age of 83, she became ill and was hospitalized for a colostomy. Her health suffered. After so long on her own, Scott, who separated from her husband some years back, moved into the home of her son Dred and daughter-in-law Katherine — a small Cape Cod-style house in Baltimore County. Within a year, she was hospitalized 19 times for dehydration. "I don't like water," Scott says. "I never have." It's not much of an explanation, but it is the only one she offers.

Katherine Scott offers her own reason for her

mother-in-law's frequent hospitalizations in 2002. "She

felt hopeless," she says. "She may have wanted to die, but

God didn't want her to leave." |

| Patient escort Loretta Gentile helps participant Geraldine Green off the van. |

As Scott's family shuttled her between the hospital and

home, the stress and uncertainty wore on everyone. Although

she was medically eligible for nursing home care, Scott

didn't want to go. After surrendering her car, her

apartment, and her friends, she clung to every bit of

freedom that remained. "I'm 84 years old," she says. "I

should be able to do what I want."

As Scott's family shuttled her between the hospital and

home, the stress and uncertainty wore on everyone. Although

she was medically eligible for nursing home care, Scott

didn't want to go. After surrendering her car, her

apartment, and her friends, she clung to every bit of

freedom that remained. "I'm 84 years old," she says. "I

should be able to do what I want."And, because of the ElderPlus program at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, she can. ElderPlus, a Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), provides community-based care to Scott and 146 other participants who live in the largely blue-collar neighborhoods nearby. The program, funded entirely through Medicare and Medicaid, does everything from transporting Scott to doctor's appointments and filling her prescriptions to making sure she takes her medicine and gets a shower. All the while, a team of doctors, nurses, social workers, dietitians, therapists, and others monitor her health and provide preventive care so that Scott can remain at home with her family and stay out of the emergency room and nursing home. "This is all-inclusive health care," says center director Karen Armacost. "We provide it. We coordinate it. If people need to see the doctor or specialist, if they need eyeglasses, dentist, or podiatrist appointments or prescriptions, all they do is come here."

"This facility has everything," Inez Scott says one late

fall morning, as she sits in the ElderPlus day health

center eating cereal. Before her sit cups of pineapple

juice, coffee, and water. All around her participants are

eating, talking, being escorted here and there for

rehabilitation therapy, eyeglasses, and help with bathing

and other forms of personal care."It's really

unbelievable," she says. |

| "We allow people to have dignified passings," says Matt McNabney. "If we can keep them out of institutions, that's important." |

Scott is tall, thin, and well turned out. Dressed this day

in a navy blue velour sweatsuit and blue angora beret, she

is a quiet presence at the center — a woman known for

her soft voice and reserved manner, for her erect bearing

and purposeful stride. People often mistake Scott for a

teacher. She doesn't mind. As she chats with a friend at breakfast, Scott smiles and laughs. She seems content with her surroundings. This wasn't always the case. Although she was tired of being poked and prodded during her frequent stays in the hospital, Scott wasn't eager to enroll in ElderPlus at first. "She didn't want to go," Katherine Scott remembers."That was where the 'old folks' go. But she had no other options." Visit ElderPlus some day and you'll see a network of offices, treatment rooms, and exam rooms that look like a typical medical clinic. Stop by the bright, airy day health center and you might catch a manicure session, a fast-paced auction, or a game of Jeopardy in progress. Listen in on the daily 8 a.m. meeting of two dozen representatives from the program's interdisciplinary team and hear them discuss in detail how patients are doing, and you'll see that it's more than a typical clinic or a senior center.

During one of those morning meetings, the staff throws open

the gray laminate doors of a dry erase board to reveal

charts detailing which ElderPlus participants are in the

hospital and the emergency room, who has fallen, and who is

in end-of-life care. Many patients have advanced chronic

illnesses, such as lung disease, cardiac disease, diabetes,

and hypertension, according to Matt McNabney, the Hopkins

ElderPlus physician and medical director. A large number of

participants also suffer from depression, he adds. The

average ElderPlus participant takes seven prescription

medications. |

| Inez Scott with ElderPlus social worker Erin Farace. Says Scott, "This place has everything." |

Quickly the staff takes stock of the hot issues that have

arisen overnight — such as the case of a new

participant who fell over the weekend and whose family is

now considering nursing home care. The team decides to call

a meeting with the family.

Quickly the staff takes stock of the hot issues that have

arisen overnight — such as the case of a new

participant who fell over the weekend and whose family is

now considering nursing home care. The team decides to call

a meeting with the family.Later at an intake and assessment meeting, held quarterly for each participant, members of the ElderPlus team go through a towering pile of fat blue binders, discussing the participants' cases in detail. Everyone — from housekeeping aides and social workers to the dietitian, doctor, and day health center nurse — offers insights as to how the participants are doing and what could be at the root of any problem they might be having. One participant, for example, lost five pounds over the last three months but says she is eating well, prompting someone on the team to ask, "What kind of stress is there at home?" Another participant has become increasingly incontinent but won't come into the day health center for showers when she's scheduled. A team member asks, "What does she like?" The response? "She's unbribable." It is the interdisciplinary team approach that makes PACE programs different from traditional health care services, Armacost says. The fact that every one of ElderPlus' 75 employees — from van drivers to housekeeping aides to escorts — is encouraged to observe participants and share their observations with the clinical staff means that medical problems can be caught earlier, chronic illnesses are better managed, and the participants can hold on to their independence longer. "Our mission is very clear," Armacost says. "We're helping people stay in their homes." "Probably 90 percent of what we see as a clinical staff is because of observations made by nonclinical staff," says McNabney."What I see in the clinic is the very tip of the iceberg. If we only had that we would miss the vast majority of medical issues."

Hopkins ElderPlus, which opened in January 1996, is one of

29 PACE programs nationwide. The Hopkins program —

the only PACE program in the state — is open only to

people age 55 and older who have been certified by the

state of Maryland for nursing home level care and who live

within a defined service area of 15 zip codes surrounding

the Bayview campus. |

| A fiber arts session at the day health center. |

ElderPlus is near its capacity of 150 people and has a

small waiting list. But because there are more frail,

elderly people in Baltimore who could benefit from the

program, Armacost says she is interested in opening a

second ElderPlus Center on Baltimore's west side. "People

don't want to be in nursing homes, and staffing shortages

present challenges in every health care setting," Armacost

says. "We have to think of developing models of care for

the elderly that are different from what we have now."

ElderPlus is near its capacity of 150 people and has a

small waiting list. But because there are more frail,

elderly people in Baltimore who could benefit from the

program, Armacost says she is interested in opening a

second ElderPlus Center on Baltimore's west side. "People

don't want to be in nursing homes, and staffing shortages

present challenges in every health care setting," Armacost

says. "We have to think of developing models of care for

the elderly that are different from what we have now."Average start-up costs for PACE programs range from $1.5 million to $2 million. The Hopkins program operates on a budget of $6 million per year. Critics of PACE describe it as an expensive "boutique" program that provides a wide array of costly services to a relatively small number of people — just 10,000 people nationwide. Supporters counter that precisely because PACE is comprehensive (and preventive), it can help avoid the need for costly nursing home care. Private nursing home care in Maryland costs an average of $5,000 per month, according to a 2002 survey by GE Financial's Long-Term Care Division. In contrast, the Medicaid payment for each ElderPlus participant per month is $2,200, Armacost says.

Beyond the finances, there are quality of life issues to

consider, says McNabney, ElderPlus' physician. In a 2001

national study that tracked where PACE participants died,

researchers found that only 15 percent of PACE participants

died in a hospital; 51 percent died at home. Nationally,

only 25 percent die at home, according to a recent study

funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. "We allow

people to have dignified and relatively peaceful passings,"

McNabney says. "If we can keep them out of institutions for

as long as possible, that's important." |

| Nurse Gladys Parra hands Inez Scott a cup of juice. Before ElderPlus, Scott was hospitalized 19 times for dehydration. |

At 8:15 a.m. one morning the ElderPlus van pulls up outside

the small white house in Turner Station that Inez Scott

shares with her son and daughter-in-law. Scott has been up

since 6:45 a.m., gotten dressed in the clothes she laid out

the night before, eaten a slice of toast, and crept out

quietly onto the heated sun porch so as not to waken her

family. She sits on the porch waiting, her teal trench coat

on, her tote bag in her lap.

At 8:15 a.m. one morning the ElderPlus van pulls up outside

the small white house in Turner Station that Inez Scott

shares with her son and daughter-in-law. Scott has been up

since 6:45 a.m., gotten dressed in the clothes she laid out

the night before, eaten a slice of toast, and crept out

quietly onto the heated sun porch so as not to waken her

family. She sits on the porch waiting, her teal trench coat

on, her tote bag in her lap.Loretta Gentile, an ElderPlus escort, gets out to help Scott board the van, but Scott doesn't need much assistance. "Good morning," Scott calls out to driver Kristi Kimble and to the handful of participants already on the van. "Good morning, Inez," participant Doris Mueller booms in a hearty, throaty voice. "It's so good to see you." Over the next 45 minutes, Scott chats with Mueller about Mueller's new purse, suffers through her corny jokes, and gracefully deflects the gift of wrapped hard candies that her seatmate keeps trying to press into her hands. The six other participants on the van listen to jazz on the radio and talk. "I think a lot of them don't have that many people to talk to," Gentile says. "They just love the fact they have a place to go where people enjoy talking to them and listening to them."

Once the van arrives at Johns Hopkins Bayview, Scott walks

into the ElderPlus Center, takes an empty white plastic box

from her tote bag and drops it into a white bin marked

"Medisets." Pharmacist Kim Luncheon will fill the box with

a week's supply of Scott's prescription medications and

have it ready for her by the time the van leaves to take

her home at about 2 p.m. |

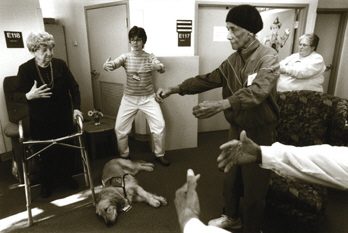

| Physical therapy assistant Anne Fraim (center) guides participants through some Tai Chi exercises. |

She walks carefully down a long ramp into the day health

center, where several dozen people with wheelchairs,

walkers, and canes (about two-thirds of participants are

female) have converged to spend the next five hours

together. Many of them are wearing hats. There's a black

sequined beret and a jaunty tam-o-shanter with a red

pom-pom, a staid khaki golf hat, and a red felt church hat

with a bow. Whether they are worn for warmth or for

fashion, all the hats tell the same story: These people

have plans.

She walks carefully down a long ramp into the day health

center, where several dozen people with wheelchairs,

walkers, and canes (about two-thirds of participants are

female) have converged to spend the next five hours

together. Many of them are wearing hats. There's a black

sequined beret and a jaunty tam-o-shanter with a red

pom-pom, a staid khaki golf hat, and a red felt church hat

with a bow. Whether they are worn for warmth or for

fashion, all the hats tell the same story: These people

have plans.Several dozen participants walk the short distance from the dining tables to the recreation area and take their seats. The activities — there are five scheduled daily — include stretching exercises, as well as orientation sessions designed to remind participants of the date, the weather, and the season. There's always a physical activity too, and a session designed to encourage memory. Today, since it's close to the holidays, the big event is a "Turkey Shoot" — a game in which participants aim a wooden gun loaded with rubber bands at a construction paper turkey pinned to a bulletin board. The better the shooter's aim, the more points he or she scores. Recreation aides Sharon Morrison and Virginia Gibson coordinate the game and the rest of the daily recreation activities with a combination of efficiency and silliness, depending on what's needed. During the Turkey Shoot, a stereo blares hits from the '70s, and Gibson encourages participants to get up and move. Doris Mueller, the joke-cracking participant from the morning van ride, and Sister Leona Williams, a nun in full habit with rosary beads tucked into her belt, giggle as they boogie to "We Are Family." Everyone is laughing and having fun, but they're also getting some much-needed exercise. "There's a lot going on here you really don't see," Armacost says, noting that all the recreational activities have a purpose beyond being purely social. In the meantime, Scott has been whisked off to rehabilitation therapy for an assessment. She then moves on to a class in Tai Chi — her first. Scott and four other participants sit in easy chairs while physical therapy assistant Anne Fraim runs them through the basic movements of the exercise. Scott stands with her arms shoulder-width apart, puts her weight on her left leg, and swings her arms forward in unison. She concentrates on breathing in and out. "It's a little harder than it looks," Fraim says as she guides Scott through the movement. She reminds Scott to take it easy."Your body just wants to keep moving," Fraim says. "This is nice and slow." Selby, the 2-year-old golden retriever who has been the ElderPlus therapy dog since May, glances up from the spot on the carpet where he's been dozing and yawns. Scott looks down at the dog and smiles. "I used to have a dog," she says. When Tai Chi class ends, Scott returns to her table for lunch. Everything on most of the other dining tables has been cleared away in preparation for the meal, and the van drivers and escorts are busy filling drink orders from the beverage cart and tying plastic bibs around necks. Scott sits down and takes a sip from a cup of juice. "I used to come five days a week, but now I'm down to four so I can have a long weekend," Scott says. There is a hint of a smile on her face. Most ElderPlus participants come to the day health center an average of three days a week. However, the care doesn't end once they're home. Some receive housekeeping services, others get visits from home health aides who assist with showering and grocery store runs. There are weekend visits and sandwich dinners sent home at night. A nurse on call is always reachable by telephone. And staff nurses and social workers visit all ElderPlus participants at home as needed. "You don't really know what you're dealing with until you see people at home," says ElderPlus home care nurse Laura Shively (Nurs '96). She's there to take blood and check on health complaints, but she's also there as an observer. (After one home visit, Shively returned to Bayview with bags of prescription medications that should have been taken but were stashed in a drawer.) She looks in their refrigerators to make sure they have enough food and checks smoke detectors to make sure the batteries are working. On a recent visit to a participant's house, Shively nearly slipped on a throw rug while walking to the kitchen sink to wash her hands. "You want me to take this to the thrift store?" she asked, holding up the blue rug. The woman, who had freshly painted pink nails and a spotless one-bedroom apartment, didn't want to see the rug go. Shively tried again. "I don't want you to have any falls," she said brightly. "If you broke a hip you couldn't live here anymore." Realizing that the old blue rug wasn't worth the risk, the participant agreed to let Shively take it with her.

It requires a lot of assistance to keep many of these

frail, elderly people in the community, but Shively insists

it's worth the work. "Even though a lot of these people are

really limited, they still have their homes, their friends,

their own time schedules," she says. "The more people lose

their independence, the sicker they think of themselves as

becoming." |

| Transportation coordinator Kristi Kimble wants to make sure Inez Scott gets safely into her house. |

After lunch and Bible study, fiber arts, and cooking

classes, the activities have come to a close, at least for

the day. Recreation aide Gibson stands at the top of the

pedestrian ramp, watching to make sure that none of the

participants heads out to the vans before his or her run is

called. She refers to most of the participants as "Honey"

or "Dear" and is free with her hugs and handholding.

After lunch and Bible study, fiber arts, and cooking

classes, the activities have come to a close, at least for

the day. Recreation aide Gibson stands at the top of the

pedestrian ramp, watching to make sure that none of the

participants heads out to the vans before his or her run is

called. She refers to most of the participants as "Honey"

or "Dear" and is free with her hugs and handholding.Gibson, who has worked at ElderPlus since 1996, has seen her share of participants come and go. She says she has loved them all. "This is their last stop — the only time they leave here is when they come into some money or they die," she says. "You have to make it worthwhile." ElderPlus participants don't "get better." The best anyone can hope for is that they remain relatively healthy, avoid the hospital, and maintain whatever skills they had when they entered the program. Using these criteria, day health center nurse Gladys Parra says she thinks the program has been good for Scott. Since she started at ElderPlus, Scott's problems with dehydration seem to be over, at least for now. "She hasn't been hospitalized for dehydration in nine months," Parra says. There is pride in her voice. Before Scott was in ElderPlus, her family worried constantly about her health, says her daughter-in-law Katherine. They still worry, only not as much. "It's been like a miracle," Katherine Scott says. With her tote bag in hand, Inez Scott makes her way out of the day health center to the ElderPlus van for the 20-minute ride back to the Scott home. The ride is quieter this time of day. The participants are tired. When the van reaches Scott's house, driver Kristi Kimble hands Scott her prescription medications and walks her to the front door. Scott takes out her key, opens the door, and walks inside. "It's good to be home," she says. Maria Blackburn is a senior writer for Johns Hopkins Magazine.

|

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231Phone 443-287-9900 | Fax 443-287-9898 | E-mail jhmagazine@jhu.edu |

|