|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

S E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 4 Alumni News

Editors: Jeanne Johnson, Philip Tang, A&S '95 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For more alumni info visit alumni.jhu.edu

Follow this link to

Send email to |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Illustration by Nicholas Wilton

Illustration by Nicholas Wilton |

Life can get pretty messy at times. Just ask Baltimore

native, best-selling author, and life coach Sunny

Schlenger.

Life can get pretty messy at times. Just ask Baltimore

native, best-selling author, and life coach Sunny

Schlenger.A professional organizer for 25 years, Schlenger's seen it all. Bedrooms filled floor to ceiling with papers and knickknacks. Grocery bags overflowing with unopened mail. Executives paralyzed by a fear of filing — and drowning in a sea of papers. Families too busy to share meals, let alone conversation. Schlenger believes there is hope for the messes — and their makers. And she's determined to tackle the time and space challenges that can make life seem so overwhelming. Her first book — How to Be Organized in Spite of Yourself (Penguin-Putnam, 1999), co-authored with Roberta Roesch — achieved Book of the Month Club fame in 1999. Schlenger was profiled in The New York Times, Fortune, USA Today, Self, and other publications, and appeared on CNN, ABC's Live with Regis, FNN, and Lifetime's Working Women's Survival Hour. The groundbreaking premise of her book — that everyone has a unique style of managing time and space — helped launch the custom-tailored approach to organization. But for Schlenger, that was only half the story. "No matter how well organized we become, we're still interested in balance and becoming who we are, where we are," she reflects. Published this May, Schlenger's new book, Organizing for the Spirit (Jossey-Bass/J.Wiley & Sons), claims there is no such thing as clutter. "Your belongings carry significance," says Schlenger. Possessions — even those unread magazines on the coffee table — are not "just things," she explains, but rather extensions of ourselves and evidence of our personal styles, needs, priorities, passions, even idiosyncrasies. Understanding that the details of your life are all connected, says Schlenger, helps those details become meaningful and manageable. "It's then possible to go beyond simple organization to find out who you are, where you are in the story of your life, how to enjoy yourself, and how to give back something," she says. Does Schlenger practice what she preaches? "They say you teach what you most need to learn," she responds, laughing. "I'm not sure whether I'm leading or following, but I'm living the life that's right for me." It's a life that is both busy and rewarding. From her New Jersey home, Schlenger coaches clients, writes a monthly e-mail newsletter, and conducts seminars and keynote presentations for Hewlett Packard, the American Heart Association, and other organizations nationwide. She is also the spokesperson for Esselte Corporation, the world's leading office supply manufacturer. With a daughter in college and a son in high school, Schlenger and her husband recently bought a home in Sedona, Arizona, where they plan to retire.

While earning her master's at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Schlenger read about a professional organizer. The field — brand new at the time — intrigued Schlenger, who was second-guessing her future as a guidance counselor. She opted to use her counseling and psychology skills as a professional organizer, helping others live productive, well-balanced lives. In doing so, Schlenger has discovered her gift — "really seeing people as they could be." She describes herself as a combination cheerleader-consultant who accentuates the positive — but only if clients are serious about getting their acts together. "People have to have a sense of humor and adequate motivation, because unless you're ready to make a change, it won't happen," she asserts.

Schlenger credits her dad, Stanley Plaine, A&S '43, for her

own motivation and zest for life. A dedicated volunteer in

his later years, Plaine died in 2003 but remains a shining

example to Schlenger that it's never too late to become who

you were meant to be.

In 1970, 20-year-old Arnie Gale, Med '76, applied to the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine with stellar credentials: excellent grades, an undergraduate degree from Stanford University, and a personal recommendation from Nobel laureate Robert Hofstadter. Still, he feared that he would be turned down because of a single detail on his application: Against friends' advice, he had acknowledged that he had muscular dystrophy. One Ivy League institution had already declined his application without an interview, and Gale feared that other medical schools would follow suit. Instead, he received word that he had been accepted to Hopkins. "In 1971, there was no Americans with Disabilities Act," Gale says. "When the medical school accepted me, it was with the understanding that what was expected of me was nothing more, but nothing less than that expected of anyone else."

Gale graduated from the School of Medicine in 1976 and,

following a residency in pediatrics at the Massachusetts

General Hospital, returned to Hopkins for another four

years to complete his training in pediatrics and neurology.

"I did what everybody else did, performing the same call

schedule and duties as my classmates and colleagues," he

says. "I've worked hard to make my disability as invisible

as possible." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disability did not deter Arnie Gale from

succeeding.

Disability did not deter Arnie Gale from

succeeding. |

Gale has spent more than two decades as a pediatric

neurologist, first as the director of postgraduate training

at the George Washington University School of Medicine and,

more recently, as a member of the clinical staff at

Stanford University. Because his muscular dystrophy is

progressive (he has used a wheelchair for the past 20

years), he has adapted his career to accommodate his

physical abilities, doing research that allows him to work

from a computer instead of interacting with patients. He

has developed a special interest in the safety of childhood

vaccines, and early this year he was awarded the Medal for

Exceptional Civilian Service by the U.S. Department of

Defense for his research on the safety of the anthrax

vaccine.

Gale has spent more than two decades as a pediatric

neurologist, first as the director of postgraduate training

at the George Washington University School of Medicine and,

more recently, as a member of the clinical staff at

Stanford University. Because his muscular dystrophy is

progressive (he has used a wheelchair for the past 20

years), he has adapted his career to accommodate his

physical abilities, doing research that allows him to work

from a computer instead of interacting with patients. He

has developed a special interest in the safety of childhood

vaccines, and early this year he was awarded the Medal for

Exceptional Civilian Service by the U.S. Department of

Defense for his research on the safety of the anthrax

vaccine.

Gale credits much of his professional philosophy to his own

childhood pediatrician. "I knew I wanted to be just like

him. He was kind, warm, and friendly. Even if I knew I was

going to get an injection, I was still excited to go."

Hélène De Beir, SAIS '98, Bol '99

A 29-year-old Belgian native, De Beir was working in Afghanistan as a project coordinator for Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), where she set up health clinics for refugees and provided first aid, vaccines, and legal assistance. A statement from Médecins Sans Frontières described De Beir as a much-loved colleague and a strong woman "who fought with passion for the rights of people worldwide," adding, "Her death has hit us hard." The attack, in the northwestern Afghan province of Badghis, was the worst on the aid community since the fall of the Taliban government. According to CNN, the attack was part of a new wave of expanded violence aimed at disrupting landmark elections in September. It was De Beir's third humanitarian mission. In 2002, she worked as a humanitarian affairs officer for Médecins du Monde (Doctors of the World) in the Afghan city of Herat. She joined Médecins Sans Frontières in 2003 to work in Africa's Ivory Coast and Iraq. She returned to Afghanistan in January of this year, first to Kabul, then Badghis. "She was so intelligent, eloquent, and talented," says her aunt, Desiree Webber-van Boxtel of Chicago. "She was successful at everything she did, and she was supposed to be a success story all the way. It's such a loss."

De Beir held a law degree from the Free University of

Brussels and specialized in international law at Hopkins'

Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).

She

planned to pursue a career as a humanitarian lawyer, with a

special interest in refugee issues. She spoke four

languages fluently and sent e-mails to friends and family

describing her experiences in the Middle East. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"She was so intelligent, eloquent, and talented," says

De

Beir's aunt, Desiree Webber-van Boxtel. "She was

successful at everything she did, and she was

supposed to be a success story all the way. It's such a

loss."

"She was so intelligent, eloquent, and talented," says

De

Beir's aunt, Desiree Webber-van Boxtel. "She was

successful at everything she did, and she was

supposed to be a success story all the way. It's such a

loss." |

In her own words, from Afghanistan in 2002: "The camps are

a disaster. People are desperately poor, babies dying every

day, crusty kids playing on old Russian tanks, tiny houses.

Despite this terrible hardship people are very friendly and

hospitable. But when they see a foreigner they think you

can solve all of their problems. They asked me if I could

repair their water-pump and if I could cure them. At that

moment you really feel like an imposter and ask yourself

what you're doing here." In another e-mail from that first mission, she wrote: "We have restriction of movement today due to security reasons, and everyone seems to be on high alert, but Herat seems relatively quiet compared to the rest of the country. Last week, as you may have seen, there was a bomb explosion in Kabul and an assassination attempt on President Karzai. Our colleagues in Kabul hardly leave their house anymore. Luckily, none of that here. So it is pretty clear that stability is fragile in Afghanistan. Sometimes the Western press speaks of 'a fragile democracy,' but that is an absolute ludicrous phrase, since we cannot really speak of a democratic system in this country. There isn't an elected central government, the regions are ruled by self-proclaimed 'emirs' (former warlords), there is not an independent judiciary, and basic human rights are not being respected." There were welcome respites from work, fear, and hardship. De Beir described weddings, dances, picnics, and the "lovely countryside" in the province of Ghor: "Mountains in turquoise, peach, pistachio, and aubergine colours were followed by green valleys in which the autumn colours offered a true spectacle," she wrote. De Beir sent only one e-mail during her last mission to Afghanistan. On March 25, 2004, in a darker tone than her previous messages, she wrote: "The situation is quite different and not that hopeful compared to nearly two years ago. In my first week here, two suicide bombers blew themselves up next to Canadian and British peacekeepers. In the last few days Herat, the peaceful city I grew attached to during my previous stay, turned into a scene of carnage (luckily I wasn't there — my team spent two nights in the basement). A lot of the instability is blamed on former Taliban elements wanting to destabilize the country's transitional government. These people are indeed ruthless; they care for nothing except for chaos and use aid workers and innocent civilians as pawns in their bloody game."

Hélène De Beir would have celebrated her 30th

birthday last June 16. In July, Médecins Sans

Frontières announced that it was pulling out of

Afghanistan — after operating continuously in that

country for 24 years — due to the failure of the

government to bring the killers to justice.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

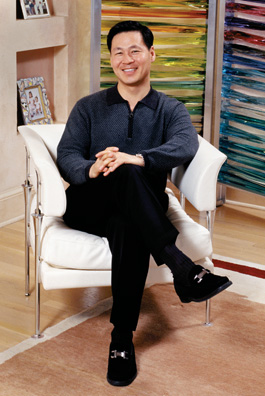

Jeong Kim's Yurie Systems sold for $1.1 billion.

Jeong Kim's Yurie Systems sold for $1.1 billion.Photo by Luisa Dipietro |

Johns Hopkins Trustee Jeong H. Kim sets high goals. When

Kim started his own company in 1992, he wanted the kind of

success many dream about, but few experience. "I wanted to

build a $1 billion company," he says, "so I did everything

consistent with that goal."

Johns Hopkins Trustee Jeong H. Kim sets high goals. When

Kim started his own company in 1992, he wanted the kind of

success many dream about, but few experience. "I wanted to

build a $1 billion company," he says, "so I did everything

consistent with that goal."Kim achieved his goal in 1998 when he sold his company, Yurie Systems, to Lucent Technologies for $1.1 billion. Kim had emigrated from Korea to the United States with his family when he was 14 and settled in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. By 16, family problems forced Kim to live on his own, and he learned to draw upon inner resolve and resiliency. "I realized I had to make something of my life," he says. In the mid-'70s, a favorite math teacher took Kim under his wing and introduced him to the up-and-coming world of personal computers. "I saw what Steve Wozniak was doing at that time — the development of Apple Computers — and I was fascinated by it," Kim says. He dreamed of building his own computer empire, but lived a different reality: school during the day; the graveyard shift at a convenience store; delivering newspapers, mowing lawns, or busing tables on weekends. The long hours and sleep deprivation left him so exhausted that once while driving on the Washington Beltway, Kim fell asleep at the wheel and only awoke when he hit a police car. A scholarship to Johns Hopkins, as part of a financial aid package, changed everything. "All of a sudden, I didn't have to worry about feeding myself," Kim says. As an engineering student, he was able to pursue his technological interests and became obsessed with building his own computer. While a student, he landed a job as a design engineer with a start-up computer company called Digitus and became an 11-percent owner (though the company went bust seven years later). After graduating in 1982, Kim joined the Navy, where he spent seven years as a nuclear submarine officer. At the same time, he worked toward a master's degree in technical management part-time at Hopkins. When he left the Navy, Kim worked as a systems development consultant and then as a satellite communications contract engineer for Allied Signal, while earning a doctorate in reliability engineering from the University of Maryland, College Park. In 1992, he started Yurie Systems, which he named after his first daughter. (His private holding company, Jurie, is named for the second.) Yurie Systems made switches that enabled digital information to travel efficiently using ATM (asynchronous transfer mode) technology. The switches solved the problem of digital congestion, allowing for the transmission of voice, data, and video using existing copper, satellite, and wireless access networks. Kim first tested the ATM switches on the battlefields of Bosnia, where, in 1996, he set up a successful satellite communications network for soldiers in the field. But he knew there could be other, commercial uses for the technology, in everything from phone signals to Internet communication. When his engineers suggested selling the company's switches for $10,000 each, Kim decided to price them at 10 times that much. And at $100,000 apiece, the coveted switches sold so fast that it was tough to keep up with demand. In 1997, Business Week featured Kim on the cover as the reigning king of "hot growth companies." Lucent Technologies thought so, too, and bought Yurie Systems for $1 billion-plus, eventually bringing Kim on board as president of Lucent's optical networking group. Today, Kim is an engineering professor at the University of Maryland and chairman of CIBERNET Corp., an emerging wireless technology services company. When marketing leading-edge technology, nothing beats the advantage of leading the pack, Kim says. And nothing can substitute for great management and engineers. But beyond know-how and hard work, Kim sees the intangible factor of luck as being critical to his success, saying, "The stars just have to align." —JJ

Photographic Freedom, Sixties-Style Political revolution may have been in the air in the late 1960s, but attorney Anthony Ilardi, A&S '67, mostly remembers an artistic revolution that took place on the Homewood campus. By some confluence of events, a group of students with a passion for photography came together on the yearbook staff. With a healthy budget from the university and no direct supervision, they were free to do what they wanted. "We were the photography geeks at an already geeky school," says Ilardi, who counts James Scott, A&S '71, Kenneth Locker, A&S '69, James Barber, A&S' 68, Carleton Davis, A&S '66, Joel Crawford, A&S '69, and Phil Heffernan among his fellow photographers. The group carried their Nikon F cameras everywhere and swapped lenses with glee. "There was a real sense of camaraderie, but it was also competitive," says Crawford, today an Amsterdam-based writer. "We all wanted to out-do each other." Instead of stiff subjects staring blankly into the camera, many portraits from the yearbooks of the late '60s convey the subject's attitude, whether querulous, tentative, contemplative, or comical. The student photographers shot at quirky angles and used dramatic, high-contrast lighting. Landscapes and still-lifes — an empty stairwell, an old sink, silhouetted trees — evoked a sense of loneliness or reverie.

"In 1967, we used full-bleed photographs, large 18-point

type, and lots of white space," says Ilardi. "I wanted to

make a strong design statement, and what we produced was

really more of a coffee table book than a traditional

yearbook." |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For the yearbook staff, the 1960s were a time of

artistic

revolution.

For the yearbook staff, the 1960s were a time of

artistic

revolution. |

It was a time of experimentation. The 1968 yearbook, for example, included a 22-page stream-of-consciousness poem in its own slipcase. Titled "End of the World Chapter," it featured a character named Buster and his contemplations on everything from abortion to a roach. The yearbook itself interspersed traditional photos with more avant-garde images, including a few psychedelic ones with trailing special effects suggestive of time-lapse photography. During a period in which photography was struggling for full acceptance as an art form, the young photographers fell under the influence of photographic greats like Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, and Henri Cartier-Bresson (known for his journalistic notion of capturing "the decisive moment," a dynamic moment of transition). "Like Cartier-Bresson, we shot a lot of film," says Crawford. "We were striving to push the button just an instant before everything came together, so that the shutter would be open to record exactly the right constellation of fleeting elements." Professor Richard Macksey, now director of the Humanities Center, offered independent projects in photography or film that encouraged the students' fledging artistic aspirations. In the 1969 yearbook, photographer Avedon's name appears among the credits, along with the names of favorite professors like Macksey, who is singled out as "the patron saint of undergraduates." And, in keeping with the times, the yearbook staff thanks "Mary Wanna, for divine guidance." Not everyone liked the magical mystery yearbook. According to Crawford, some students crusaded to pull the plug on the venture and, by 1969, funding was cut back. The indignant rebels responded by reducing the descriptive content for seniors, and only identified seniors by last name. That editing choice only further inflamed passions. "There are probably people who are angry about that to this day," says Crawford. By 1970, the yearbook resumed its former function of codified documentation. But Crawford, who admittedly misses the '60s, waxes philosophical. "It was fun while it lasted," he says. "It was a time of new ideas and great excitement. A new culture was being born in the midst of a terrible war, and the two events were not unrelated. Despite the war, I think it was a time of great optimism, a time when anything was possible." —JJ

The Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced

International Studies |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jessica Einhorn

Jessica EinhornPhoto by Kaveh Sardari |

SAIS was

established in 1944 to prepare a new generation of

leaders for the demands of a volatile world. Sixty years

later, SAIS' mission hasn't changed, but the world around

it has. As the school prepares to celebrate its 60th

anniversary next month, Johns Hopkins Magazine

asked Dean Jessica Einhorn where SAIS is and

where it's going.

SAIS was

established in 1944 to prepare a new generation of

leaders for the demands of a volatile world. Sixty years

later, SAIS' mission hasn't changed, but the world around

it has. As the school prepares to celebrate its 60th

anniversary next month, Johns Hopkins Magazine

asked Dean Jessica Einhorn where SAIS is and

where it's going.You've said recently that this is a pivotal time for SAIS. Why? It's broadly accepted that two events marked the end of the era for which the Nitze School was created: the fall of the Berlin Wall, which symbolized the end of the Cold War, and the 9/11 attacks, which changed our understanding of threats to the United States. Those two signal events occurred against a background of globalization, rising Asian economies, and intractable poverty in Africa, South Asia, and elsewhere. If you look at both the big trends and the major events, you see that this is a remarkable time for a place like SAIS. How is SAIS rising to meet the challenges of this new era? First, we've put all the building blocks in place for educating future leaders: a strong emphasis on economics, core functional disciplines such as strategic studies and international relations, robust regional programs, and foreign language requirements. These are the essentials for meeting the demands of a changing world. Second, we're alert to new needs and opportunities. For example: We recently established a program in South Asia studies. We're taking our renowned program in Japan studies and broadening it to give explicit attention to Korea. We're creating a chair in Latin American studies. We're laying the groundwork for a new program in energy, environment, science, and technology. And — given the increasing influence of the media — we're considering how to mentor students interested in journalism. What are your critical needs for the future? More than anything, we need to invest in our people. Our faculty leaders are the all-important front line for educating students. But we're experiencing some turnover in our senior ranks and have to go out and recruit new great scholars and teachers. We have some really illustrious faculty in chairs who are totally without endowed funding, and quite a few others sitting in chairs that are underfunded. All our programs should have at least two full-time faculty — one senior and one junior — but that's not the case now. Tuition costs keep going up for our students. SAIS doesn't have the challenge of providing residential facilities, but we feel the pressure indirectly because financial needs rise as housing costs climb. Across the board, we have this relentless increase in cost, which requires an increase in financial aid. Also, we must modernize our infrastructure. We need good space where our students can learn, our faculty and staff can function well, and our many distinguished visitors can participate in our educational experience. SAIS is, in many ways, a dream for a dean: great faculty, great administration, and wonderful student body. The responsibility to enable these people to fulfill their potential — that's the challenge that's on my mind every day.

MSN Money columnist Michael Brush, Bol '89, earned a "Best in Business" award from the Society of American Business Editors and Writers for a series of columns about the unfair tactics employed by Wall Street insiders. Winning column topics included "How insiders can unload stocks in secret," "You're fired. Here's your $16 million," and "Wall Street plays dirty despite the clean-up effort." In June, world-renowned ophthalmologist Arnall Patz, A&S '98 (MA), received the Presidential Medal of Freedom — the nation's highest civilian honor. Patz, the former director of Johns Hopkins' Wilmer Eye Institute, conducted breakthrough research that helped to prevent blindness and developed one of the first lasers used to treat eye disease. In 1998, at age 78, Patz earned Hopkins' master of liberal arts degree. Michael A. Moore received the American Heart Association's prestigious 2004 Physician of the Year award, which recognizes outstanding contributions to reducing disability and death from cardiovascular disease and stroke. Moore, who completed his post-graduate fellowship at Johns Hopkins in 1974, manages the Hypertension Clinic within the Family Healthcare Center of Danville, Virginia. In August, William Stromberg, Engr '82, became the first Johns Hopkins football player ever to be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Stromberg, a wide receiver who played from 1978-1981, set school and NCAA Division III career records at Hopkins for receptions (258), receiving yards (3,776), and touchdowns (39).

Reunion 2004 During the last weekend of April, as the class of 2004 counted down the days to commencement, thousands of Johns Hopkins alumni from the schools of arts and sciences and engineering returned to campus to celebrate one of the university's most popular annual traditions — Homecoming at Homewood. Members of 15 reunion classes from 1929 to 1999 were reunited over the course of an action-packed four-day weekend. Here are just a few of the moments the Alumni Association caught on film.

Visiting Writing Seminars professor and actor John Astin, A&S '52, speaks to alumni about life beyond The Addams Family.

Members of the Class of 1929 celebrate a Johns Hopkins first — a 75th reunion.

Members of the Class of 1974 participate in the Parade of Classes prior to the lacrosse game between Johns Hopkins and Towson. 1974 marked the graduation of the first JHU class to include women who enrolled as freshmen.

Members of the Class of 1999 return to Johns Hopkins to celebrate their fifth reunion.

University President William R. Brody presents Irv Kelson, Engr '54, with a commemorative medallion. Kelson and classmates celebrated their 50th reunion.

Four Hopkins bands from the 1970s — Ocean Rose, The Reason (pictured above), Zumbuzi, and Rodeo Rick — got back together for a special reunion performance in Levering's Great Hall.

Joseph Reynolds, president of the Alumni Association, presents the Class of 2004 with its official class banner. The ceremony was followed by a senior class dinner sponsored by the Alumni Association.

The Blue Jays beat Towson 13-8 in the annual Homecoming lacrosse game at Homewood Field.

Vincent Mettle, SPSBE '00 (MBA), and his family enjoy a School of Professional Studies in Business and Education tailgate party prior to the Homecoming lacrosse game.

Members of the Peabody Conservatory class of 1954 celebrate their 50th reunion at a Peabody Homecoming brunch.

The Alumni Association has just unveiled the exotic destinations in the 2005 Alumni Travel Program. The travel program offers alumni trips all over the world — many with Johns Hopkins faculty — that combine leisure and sightseeing with the university's commitment to lifelong learning. For more information and a complete list of 2004 and 2005 trips, visit www.alumni.jhu.edu/travel.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231Phone 443-287-9900 | Fax 443-287-9898 | E-mail jhmagazine@jhu.edu |

|