|

|

NOVEMBER 2000 CONTENTS

|

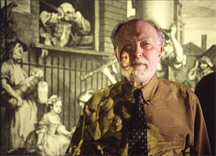

| Ronald Paulson, the world's expert on matters Hogarthian, has generated a profoundly new portrait of the 18th-century artist who found Beauty in all the "wrong" places. |

A Scholar's Progress

By Dale

Keiger

Photograph by David Owen Hawxhurst

William Hogarth, the 18th-century English painter and engraver, has been the nexus of four decades of scholarly work by Paulson, the Mayer Professor of Humanities at Hopkins and the world's primary scholar on matters Hogarthian. When Paulson examines Jonathan Swift, he comes back to Hogarth. When he reads Henry Fielding, he comes back to Hogarth. When he ponders the development of aesthetics as a philosophical discourse, he comes back to Hogarth. "I've come to believe that he's a central figure of English culture in the 18th century," Paulson says. He's certainly been the central figure in Paulson's intellectual life.

In 1993, Paulson published the third and concluding volume of Hogarth (Rutgers University Press, 1991-93) his 1,455-page biography of the artist. Twenty-two years before that, he had published another, shorter biography titled Hogarth: His Life, Art, and Times. Already an English scholar, Paulson trained himself as an art historian to better appreciate Hogarth's work. And Paulson has found that in his other books, such as The Beautiful, Novel, and Strange: Aesthetics and Heterodoxy (Johns Hopkins, 1996), Don Quixote in England: The Aesthetics of Laughter (Johns Hopkins, 1998), and The Life of Henry Fielding (Blackwell, 2000), the index entry for "Hogarth" is inevitably long.

Until Paulson set to work, Hogarth had been consigned to a back shelf, as an English portrait painter of no great significance and an engraver with a taste for the common life observed on the streets of London. When, as a graduate student in the 1950s, Paulson tried to find copies of Hogarth's engravings in the Yale University library, he discovered that the only reproductions were of bad 18th-century re-engravings. Paulson himself did not begin looking at the artist with great expectations. "When I started this I was diffident about his work, partly because everyone else was diffident about him," he recalls. But the more Paulson studied the artist and his milieu, the higher his estimation became. "Hogarth the good old boy is the old picture," he says. "The Hogarth I came up with is someone intellectually on the level with Swift and Richardson and Fielding."

|

| The third plate of A Rake's Progress." Hogarth turned away from copying classical sculptures and protrayed instead the robust daily life around him in London. |

When he began serious study of Hogarth in the 1960s, Paulson encountered resistance. He had found that there was no catalog of the artist's graphic works, so he set out to write one. He submitted it to the University of Illinois Press, but a reader for the publisher responded, "I can imagine doing this for Rembrandt or Dürer, but not Hogarth. I might want to have the book myself, but I can see no reason for publishing it." So Paulson took the manuscript to Yale, which brought it out in 1965.

His fascination with Hogarth led to Hogarth: His Life, Art, and Times (Yale, 1971). Then he spent a good bit of the next 20 years rethinking the artist and publishing much revisionary material, until he finally produced the three-volume Hogarth, which Paulson considers less of a standard biography and more of "an old-fashioned 'Life-and-Works' and 'Life-and-Times'" history.

For the biography, Paulson spent a year in England poring over archival material: parish birth records, tax records, correspondence (what there was of it--Hogarth apparently wasn't much of a letter writer). He went page-by-page through every newspaper published in London from 1680 to the 1780s. "My eyeballs became calibrated until certain names just lit up," he recalls. The newspapers were vital for, among other things, dating Hogarth's engravings.

Though he was a fluent painter of oils, Hogarth's end product was his engravings, many of them satirical and narrative, like A Harlot's Progress and A Rake's Progress. He would paint a new work, then offer copies to the public for subscription. If you wanted to buy a copy, you subscribed by paying half the asking price before Hogarth had completed the engraving of the new painting, and half when you picked up the finished product. The artist got the word out to the public through the newspapers. "He was a great advertiser," Paulson says. "He advertised everything." Each time he found an ad in a London paper, Paulson could date another engraving.

|

| In A Harlot's Progress, an innocent girl named Hackabout comes to the big town (top) and falls into the cruel hands of the Bawd Mother Needham. The innocent maiden's downfall ensues, and by the sixth and final picture, Hackabout is dead. |

Studying advertisements led Paulson to other discoveries. For example, he happened across an advertisement, published in 1708 in the Daily Courant, for a nostrum of some kind, with which to treat children for "the GRIPES in Young Children, and prevents FITS." The advertiser was Hogarth's mother, but the address puzzled Paulson. He had believed that Hogarth's father, Richard, was running a coffee house at the time, a coffee house that specialized in Latin conversation. The business was located in St. John's Gate, and the Hogarth family lived in a room there. But the advertisement read, "Sold only By Mrs. Anne Hogarth next Door to the Ship in Black and White Court, Old Bailey." The address was part of the Fleet Prison. Apparently, Richard's coffee house had failed and he had been imprisoned for his debts; from somewhere he had found enough money to live outside the actual prison, but within an area known as "the Rules," in a sort of house arrest with his family. No one had known this about Hogarth's family until Paulson noted Mrs. Hogarth's advertisement.

"Almost every day I made a discovery," Paulson says. He sometimes found records that their owners didn't know they had. For example, he asked the venerable insurance company that had insured the Hogarths if he could see their records. "They said, 'We have nothing.' But they let me go down into the vault, which was like the sewers of Paris. On my first day, I found everything on Hogarth and his family."

Hogarth was born in London in 1697, the only surviving son (there were two daughters) of Richard, a minor classical scholar and schoolmaster, and Anne. Young William took a lively interest in the street life outside the Hogarths' door, and amused himself by sketching the characters he saw. At age 15, he became an apprentice to a silversmith, but found the work unsatisfying. By age 23, he was on his own, trying to make his way as a copper engraver, illustrator, and painter.

The three volumes generated by Paulson's exhaustive research document virtually all that is known about Hogarth. Paulson wryly observes, "I can't think of too many people reading all of them." Peruse the many pages and you'll learn that Hogarth recalled that in school he "drew the alphabet with great ease." That in 1730 or '31, he accepted a commission for a portrait from a Mr. Sarmond, after accepting commissions from Sir Robert Pye and John Thomson. That in the 1740s Hogarth was said to be making £12 per day from etchings. Still, Paulson says, there are aspects of the artist's life that remain murky. "I would like to know more about his married life. I could find nothing that indicated he'd ever gone to church, though his wife certainly did." And, as Paulson writes in Vol. I of Hogarth, it remains a mystery who first turned the young Londoner toward art.