| |

Wholly Hopkins

Matters of note from around Johns Hopkins

University: In the wake of attacks, university

mourns

University: In the wake of attacks, university

mourns

Astronomy: Observing the heavens from a desktop

Astronomy: Observing the heavens from a desktop

University: Lead study fallout lingers

University: Lead study fallout lingers

Homewood: Cancer trial in India draws fire

Homewood: Cancer trial in India draws fire

Nursing: Addressing a hidden killer in South

Africa

Nursing: Addressing a hidden killer in South

Africa

Art History: Of sprites earthy and sublime

Art History: Of sprites earthy and sublime

Health: Physician, heal the system

Health: Physician, heal the system

Biomedicine: New efforts to engineer tissue begin to

gel

Biomedicine: New efforts to engineer tissue begin to

gel

Historic Houses: A palette for life's

lessons

Historic Houses: A palette for life's

lessons

Alumni: Catching up with Greg Drozdek '95

Alumni: Catching up with Greg Drozdek '95

In Memoriam: A voice that will be missed

In Memoriam: A voice that will be missed

University

In the Wake of Attacks,

University Mourns

As twilight faded into purple darkness on September 13, two

days after the fateful attack on America, hundreds of Johns

Hopkins students, faculty, and staff gathered as one

community on Homewood's Upper Quad. While some bowed their

heads in prayer, others embraced tearfully or stared

uncomprehendingly into the cool night air.

The diverse gathering--some 1,500 strong of Jews,

Muslims, Christians, and Hindus--shared an intimacy born of

collective grief. From her spot on the steps of Gilman Hall,

university chaplain Sharon Kugler,

with President William R. Brody,

led those assembled in seeking the courage to move forward:

"May we offer the power of our sorrow to the service of

something greater than ourselves," she said. "We must

understand that acts of terror are not religious acts. They

are shameless acts of evil and ignorance."

|

Scenes from the vigil held on the Homewood

campus

Photo by Jay Van

Rensselaer |

As the vigil drew to a close, many moved to the Gilman

Hall steps to lay white carnations, symbols of the miracle

and sanctity of life. And they lingered. Kugler would say

later, "I was amazed at the number of people who stayed

after. There was this yearning to keep connected with other

people who are also feeling this tragedy so intensely--a

certain kind of intimacy that we all shared."

As the vigil drew to a close, many moved to the Gilman

Hall steps to lay white carnations, symbols of the miracle

and sanctity of life. And they lingered. Kugler would say

later, "I was amazed at the number of people who stayed

after. There was this yearning to keep connected with other

people who are also feeling this tragedy so intensely--a

certain kind of intimacy that we all shared."

There would be other opportunities for members of the

Hopkins community to join together, including a student-led

prayer service the next day, initiated by leaders of the

Muslim student group; a march for peace over the weekend,

involving students from several area colleges and ending in

front of the Homewood campus; jam-packed religious services

for students of every faith at the Bunting-Meyerhoff

Interfaith Center; and, several weeks after the tragedy, a

Speak Out Against Hatred event at the Glass Pavilion,

sponsored by members of SEED (Students Educating and

Empowering for Diversity).

For those touched personally by the tragedy--there are

Hopkins students who lost parents, cousins, an uncle, and

close friends--the wounds are still raw, the grieving

process just begun.

But Kugler, and others, draw some measure of hope from

the way members of the Johns Hopkins community united at the

September 13 vigil to mourn and gain strength from one

another. "It isn't something we do easily here at Hopkins,

to take ourselves away from our duties, our jobs, our

intellectual pursuits," said Kugler. "But on that Thursday,

because we gathered, we gave ourselves permission to do it."

--Sue De Pasquale

University

Wolfowitz Ponders Legacy

of Terrorist Attacks

"The whole civilized world has been shocked by what has

happened, and some elements of the uncivilized world are

beginning to wonder if they are on the wrong side. We have

unfortunately entered a new era, and we are going to be

sorely tested," said U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul

D. Wolfowitz, former dean of Hopkins's

Nitze School of Advanced

International Studies, at a Pentagon press conference

after the September 11 terrorist attacks on New York and

Washington.

Astronomy

Observing the Heavens

from a Desktop

In the 19th century, astronomers put their eyes to

telescopes and sketched what they saw, one object at a time.

They were restricted to visible light--to draw it, they had

to see it. Then photography began recording images, and film

became the data collector; faster and more sensitive, film

expanded the astronomer's spectrum somewhat past the visible

range at the red and violet ends. Now instruments that can

detect a vast range of the spectrum--visible light,

infrared, ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays, radio waves--are

conducting comprehensive astronomical surveys and gathering

information digitally at extraordinary speed. The result is

a tsunami of data. "It's becoming increasingly easier to

collect data than to make sense of it," says Alex Szalay.

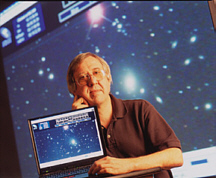

|

Szalay: harnessing a tsunami of data

Photo by Mike

Ciesielski |

So Szalay, Hopkins professor of

astronomy and a

principal collaborator on the

Sloan Digital Sky Survey

(Hopkins Magazine,

April 2001), has become one of the prime movers behind

the National Virtual Observatory. The NVO, as envisioned by

Szalay and fellow astronomers and computer scientists at

nearly two dozen institutions, will be a digital network

linking astronomers, observatories, astronomical databases,

and educational institutions. The network will permit almost

any desktop computer to become a sophisticated virtual

observatory.

So Szalay, Hopkins professor of

astronomy and a

principal collaborator on the

Sloan Digital Sky Survey

(Hopkins Magazine,

April 2001), has become one of the prime movers behind

the National Virtual Observatory. The NVO, as envisioned by

Szalay and fellow astronomers and computer scientists at

nearly two dozen institutions, will be a digital network

linking astronomers, observatories, astronomical databases,

and educational institutions. The network will permit almost

any desktop computer to become a sophisticated virtual

observatory.

The National Science Foundation just awarded the

project a $10 million grant. Institutional players include

Hopkins, the California Institute of Technology, and the

Space Telescope Science Institute.

Says Szalay, "An astronomer used to get some telescope

time, collected data, brought the data tapes back to his own

computer, and made sense of it there." Now, he says, a

single night's observation may produce so much data the

astronomer cannot, in effect, carry it all away. The planned

Large Synoptic Survey Telescope will produce more than 10

petabytes of data per year by 2008--that's 10 million

gigabytes from a single instrument. (In comparison, a

typical desktop Mac or PC will have a hard drive of 20 to 30

gigabytes.)

Compounding the problem, says Szalay, is that this data

is not static. The sky changes day by day because everything

is in motion. Plus, astronomers must constantly apply

corrections to their data to account for things like

atmospheric effects and optical distortion. With each

refinement, the dataset changes.

Several challenges must be tackled before the NVO can

come to fruition. Scientists need to develop a common format

for their databases, so that data collected from, say, the

Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory are

accessible to any astronomer in the world and can be

manipulated by common tools. Someone has to write code to

retrofit existing databases to a new standard. Such huge

fields of data will require vastly more efficient databases

and faster, more precise search engines, to enable rapid

data searches, sorts, and retrievals. To handle the

statistical analyses, scientists will need better algorithms

to crunch massive amounts of data. Says Szalay, "We can't

throw a billion computers at it. We need more clever ways to

work with the data." Finally, the NVO will need rapid data

transmission capabilities ... a very wide pipe, in Internet

parlance.

Now that significant funding is in place, says Szalay,

"we need to do a lot of small things first, to make sure we

are on the right track." There will be, says Szalay, a lot

of meetings: "If you lock a lot of smart people in a small

room, good things come out of it." --Dale Keiger

University

Lead Study Fallout

Lingers

An August ruling made by the Maryland Court of Appeals

raised important questions about the future of public health

research involving children. At issue: Is it ethical to

enroll children in clinical trials that could pose risks?

The case involves a

Kennedy Krieger

Institute study of low-cost lead abatement efforts in

East Baltimore, where an estimated 95 percent of homes have

high lead levels. For the small children living in these

homes, lead exposure can be devastating, contributing to

brain damage, reduced intelligence and attention span,

hearing loss, and learning and behavior problems.

The three-year study, conducted from 1993 to 1995, was

led by Mark Farfel, a researcher at Hopkins's

Bloomberg School of Public

Health. The study looked at whether less expensive

abatement strategies could be effective in reducing lead

hazards. Researchers found that even minimum strategies--

such as limited repainting, professional cleaning to remove

lead dust, and stabilizing of exterior lead paint--

significantly reduced home lead levels and led to a lasting

reduction in children's elevated lead levels, to below the

"level of concern."

According to Kennedy Krieger officials, the study

ensured that the families in the study had vastly less lead

exposure than other families in the neighborhood. Children

also received regular blood tests and medical check-ups,

said Gary Goldstein, Kennedy Krieger president.

But two mothers brought suit against Kennedy Krieger,

charging researchers had allowed their children to live in

homes with incomplete removal of old lead paint, and that,

as a result, their children suffered brain damage.

In ruling that the suits could move forward, Maryland

Court of Appeals judge Dale Cathell compared the Hopkins

study to the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment and to

experiments inflicted upon prisoners at Buchenwald during

World War II. The strongly worded ruling prohibited any

future medical experiments on children that pose "any risk"

and that do not directly benefit the children.

"This decision could have enormously broad

implications, because almost all studies involve risk,"

responded Hopkins University President William R. Brody.

Bloomberg School of Public Health Dean Alfred Sommer

criticized the ruling for implying that human subjects in

nontherapeutic trials "have nothing to gain and everything

to lose." Noted Sommer, "If that were a meaningful

distinction, most public health research, which aims to

prevent disease in the first place, would never be done,"

including the Salk polio vaccine.

Worried that the court's ruling could shut down many

pediatrics studies and drive research dollars out of the

state, Hopkins, Kennedy Krieger, University of Maryland

Medical System, and the Association of American Universities

in September asked the appeals court to modify its ruling,

changing "any risk" to "minimal risk," the language used in

federal regulations of human studies. In October, the court

modified the language as requested, making it possible for

many pediatrics studies to move forward.

But the court refused to back off from its reference to the

infamous Tuskegee studies. --SD

Homewood

Cancer Trial in India

Draws Fire

A clinical trial of an anti-cancer drug in India has drawn

the scrutiny of Johns Hopkins University officials after

physicians in India raised questions about the manner in

which the study was conducted.

The researcher was identified in a July 31, 2001,

Baltimore Sun article as Ru Chih C. Huang; Huang has

served on the biology

faculty of Hopkins's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences

since 1965. (Because of confidentiality policies, university

administrators did not release Huang's name and will neither

confirm nor deny her involvement.)

Conducted in 1999 and 2000, the clinical trial involved

26 cancer patients in Kerala, India. The study aimed to

determine whether a chemical derived from the creosote plant

could stop the growth of oral cancer.

In March, Hopkins officials learned that the principal

investigator of the study had not obtained approval from a

Hopkins institutional review board (IRB). The researcher

assured administrators that the study protocol had been

approved by appropriate authorities in India and that proper

informed consent was obtained.

According to the Baltimore Sun article, Huang

said she did not realize the university requires internal

approval of experiments abroad. "I will never do it again in

this way. But certainly I did not hurt the people in that

country in any way, and I think that this will prove to be

an effective anti-cancer drug," Huang is reported as

saying.

In March, the university counseled that the Hopkins

internal review should have been obtained and that a

proposed follow-up study would have to go before a Hopkins

IRB.

In mid-July, the Indian press reported allegations made

by physicians at the Regional Cancer Center in Kerala that

raised serious questions regarding how the cancer study was

conducted. The reported allegations included concerns about

whether proper informed consent had been secured, whether

the drug had been properly screened for toxicity, and

whether surgery or other conventional treatment had been

unnecessarily delayed.

After the accounts surfaced in the press, Hopkins

officials launched a preliminary inquiry which later

confirmed that the cancer study had not been reviewed or

approved by any of the university's IRBs.

The university convened an investigative panel "to

conduct a formal investigation to more fully develop the

facts." At press time, the investigation was not yet

concluded.

During the course of the investigation, the faculty

member in question has been directed by university officials

to stop all follow-up work related to the study.

--SD

Homewood

North Addresses Nuclear

Threat During MSE Symposium

"It's time to get a grip, to wake up to the fact that we've

been manipulated by the media. These stories about people

bringing in nukes in suitcases are about as likely to happen

as a meteor striking [Shriver Hall]. In order to put a nuke

in a suitcase, you'd need a W-88 warhead, the same warhead

the Chinese stole from Los Alamos. The Chinese have a ton of

money and intelligence and they still can't figure out how

to use it. Do you really think bin Laden's gonna figure it

out in a tent in Afghanistan?" scoffed Lt. Col. Oliver North

on September 27 in the second talk of this year's

student-run Milton S. Eisenhower

Symposium. The symposium's original theme, "A Nation

Divided: Politics and Power in the 21st Century," was

changed to "A Nation United..." after the September 11

attacks. Those slated to speak included Washington

Post writer Bob Woodward, civil rights activist Lani

Guinier, and U.S. Senator Russ Feingold.

Nursing

Addressing a Hidden

Killer in South Africa

It is winter in Cape Town, South Africa, and a slight chill

invades the August air. In the black township of Crossroads,

just outside the city limits, the weak morning sunlight has

yet to burn off a low-hanging haze. Men, women, and children

wearing jackets and heavy sweaters gather in front of the

local government-funded clinic waiting for it to open. If

they are lucky, they will see a physician or nurse before

the day ends. If not, they will go home and return

tomorrow.

It is winter in Cape Town, South Africa, and a slight chill

invades the August air. In the black township of Crossroads,

just outside the city limits, the weak morning sunlight has

yet to burn off a low-hanging haze. Men, women, and children

wearing jackets and heavy sweaters gather in front of the

local government-funded clinic waiting for it to open. If

they are lucky, they will see a physician or nurse before

the day ends. If not, they will go home and return

tomorrow.

The clinic sits in the heart of the township, amid

homes that range from one-room makeshift shacks with no

electricity or running water to modest dwellings made of

cinderblocks.

|

Cape Town residents wait to be seen at the

clinic.

Photo by Allen

Jefthas |

This particular morning follows a day of rioting that

took place near Crossroads. Gunfire erupted when hundreds of

black South Africans protested the poor living conditions in

an informal housing settlement. Police exchanged gunfire

with protesters, and the incident snarled traffic for hours.

Now, close to 24 hours later, most of the violence from the

protest has subsided, but rubble still litters some streets

and a few impromptu fires are still smoking.

This particular morning follows a day of rioting that

took place near Crossroads. Gunfire erupted when hundreds of

black South Africans protested the poor living conditions in

an informal housing settlement. Police exchanged gunfire

with protesters, and the incident snarled traffic for hours.

Now, close to 24 hours later, most of the violence from the

protest has subsided, but rubble still litters some streets

and a few impromptu fires are still smoking.

On their way by car to the Crossroads township are

nurse researcher Martha Hill, interim dean of Hopkins's

School of Nursing,

and physician Krisela Steyn, director of the Chronic

Diseases Lifestyle Program at the South African Medical

Research Council (MRC).

The two have joined forces to chip away at one of black

South Africa's greatest health risks: cardiovascular

disease. Hill has spent the past two weeks in Cape Town,

where she is overseeing completion of the first leg of a

study to control hypertension in black South Africans.

|

Nursing student Stacie Stender takes a patient's

blood pressure.

Photo by Allen

Jefthas |

Next to AIDS, hypertension and cardiovascular disease

are the biggest killers of South Africans. According to MRC

researchers, about 10 percent of South Africans die each

year from heart disease; that figure might be as high as 25

percent because of inaccurate reporting of deaths in black

townships. More than 25 percent of South Africans have high

blood pressure, and a lack of knowledge about the condition

is particularly prevalent in the townships, where awareness

about hypertension gets lost in the shadow of AIDS, which

has hit South Africa harder than any other country in the

world. One in nine South Africans now tests positive for

HIV/AIDS.

Next to AIDS, hypertension and cardiovascular disease

are the biggest killers of South Africans. According to MRC

researchers, about 10 percent of South Africans die each

year from heart disease; that figure might be as high as 25

percent because of inaccurate reporting of deaths in black

townships. More than 25 percent of South Africans have high

blood pressure, and a lack of knowledge about the condition

is particularly prevalent in the townships, where awareness

about hypertension gets lost in the shadow of AIDS, which

has hit South Africa harder than any other country in the

world. One in nine South Africans now tests positive for

HIV/AIDS.

Raising awareness about hypertension in hard-to-reach

populations is nothing new for the energetic Hill. For more

than 10 years she has researched ways of controlling

hypertension in young, urban, African-American males. With

colleagues from other divisions within Hopkins, Hill devised

a model of personalized care using a team of nurse

practitioners, physicians, and community health workers. The

model, which aggressively tracks men with high blood

pressure, succeeded in controlling the hypertension rates of

almost 40 percent of a group of 309 African-American men in

East Baltimore. With a grant from the Fogarty International

Center of the National Institutes of Health, Hill is working

with MRC researchers to replicate the Baltimore hypertension

study in three South African townships. As part of the

School of Nursing's Global Health Promotion Research

Program, Hill had three students assisting with the study.

They spent the summer working in the Crossroads clinic,

developing questionnaires that determine the barriers

preventing black South Africans from controlling their

hypertension.

"It's a real challenge," says Hill as she walks through

the crowded Crossroads clinic. "If you ask people what is

high blood pressure, they have many different ideas and

don't always understand the lifestyle relationship."

|

Martha Hill and South African nurse researcher Thandi

Puaone check out one of the city's popular grills, featuring

fat-laden and salty meats.

Photo by Kate

Pipkin |

In a small room at the clinic, Hill watches closely as

Hopkins nursing graduate student Stacie Stender measures the

blood pressure of William Qomoyi. It is 175/90--well above

the "normal" range of 140/80. Stender tests it again to be

certain. Qomoyi claims that because he drinks a traditional

beer brewed in the township, he does not have high blood

pressure--a belief held by more than one patient. Stender

makes arrangements for him to get a prescription for blood

pressure medication, then hands him a loaf of bread as

thanks for participating in the study and calls in the next

patient. This man's blood pressure tops out at 225/110.

In a small room at the clinic, Hill watches closely as

Hopkins nursing graduate student Stacie Stender measures the

blood pressure of William Qomoyi. It is 175/90--well above

the "normal" range of 140/80. Stender tests it again to be

certain. Qomoyi claims that because he drinks a traditional

beer brewed in the township, he does not have high blood

pressure--a belief held by more than one patient. Stender

makes arrangements for him to get a prescription for blood

pressure medication, then hands him a loaf of bread as

thanks for participating in the study and calls in the next

patient. This man's blood pressure tops out at 225/110.

Hill and her students encountered other cultural

beliefs besides the traditional beer "cure." Many residents

of black townships are reluctant to have their height

measured, since they think it means they are sick and being

measured for a coffin. A particularly deadly belief among

black South African women is the idea that obesity is a

desired state; being large is associated with being

dignified, well-off, AIDS-free, and healthy.

Hill is quick to point out that cultural practices are

not the only barrier to controlling hypertension. Lifestyle

changes are also to blame. After apartheid was abolished in

1994, many rural black South Africans moved to urban areas

such as Cape Town in search of work and a better life. So

far, city living has only given them a more sedentary

lifestyle complete with poor diet. Vendors set up crude,

homemade grills on street corners in the townships where

they fry up fatty, salty cuts of meat to sell at a low cost.

It is a popular meal among black South Africans with limited

income.

The better quality of life sought by so many is proving

elusive. According to nurse Zodwa Maxhama, who works in the

Crossroads clinic, many older blacks watched their children

die of AIDS and now have become the primary caregivers for

their HIV-positive grandchildren. "They have a great deal of

stress," says Maxhama. "They have no job, no food, and

family problems." Against this backdrop, controlling

hypertension often falls to the bottom of the priority

list.

Notes Hill, "Often the people who have hypertension are

the ones who are working and carrying the already-fragile

economy. If the head of a household has a stroke, the toll

in death and disability ends up having a socioeconomic

impact. Prevention is the key."

Hill hopes the model she is trying to implement will

make a difference, despite the overwhelming hypertension

rates: "As nurses, we tend to be passionate about care, but

unless you have good data to back it up, you will have

little effect on changing practice." --Kate Pipkin

Art History

Of Sprites Earthy and

Sublime

In 15th-century Italy, the sculptor Donatello reached back

to antiquity for a decorative figure: a nude, winged young

boy found on ancient Roman sarcophagi. The figure has lasted

to this day as Cupid, the diminutive archer of love. But in

the art of Renaissance Italy, says Charles Dempsey, Hopkins

professor of art history, these

figures, called putti, represented a much wider assortment

of spirits. They were central to the melding of the

classical and the vernacular that is at the heart of

Dempsey's view of Renaissance art.

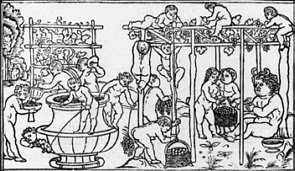

|

|

From the George Peabody Library collection,

Spiritelli Harvesting the Grape, a woodcut from

Francesco Colonna's book Hypnerotomachia Polifili

(Venice, 1499). |

"The art of the Renaissance period has normally been

characterized as having to do with the revival of

antiquity," says Dempsey. "My argument is that in Italy

there are two deep cultural traditions. One is indeed the

ancient tradition. But the other is the vernacular

tradition, which is the tradition of poetry and art created

in native Italian, so to speak, from the time of Dante,

Petrarch, and Boccaccio." The putto, Dempsey says, is an

example of such vernacular expression. "It does derive, to

be sure, from ancient Roman sarcophagi, but at the same time

it's defined by this term spiritello"--spirit, or sprite--

"which is a term that only has meaning in the native

Italian. It doesn't have any Latin equivalent."

"The art of the Renaissance period has normally been

characterized as having to do with the revival of

antiquity," says Dempsey. "My argument is that in Italy

there are two deep cultural traditions. One is indeed the

ancient tradition. But the other is the vernacular

tradition, which is the tradition of poetry and art created

in native Italian, so to speak, from the time of Dante,

Petrarch, and Boccaccio." The putto, Dempsey says, is an

example of such vernacular expression. "It does derive, to

be sure, from ancient Roman sarcophagi, but at the same time

it's defined by this term spiritello"--spirit, or sprite--

"which is a term that only has meaning in the native

Italian. It doesn't have any Latin equivalent."

Dempsey makes his case in a new book, Inventing the

Renaissance Putto (University of North Carolina Press,

2001). To the Renaissance audience for art, the putti were

not just little gods of love, but spiritelli, the

spirits that animate bodily functions, muddle the head after

the consumption of wine, and cause involuntary reactions

such as fright or sexual arousal.

Dempsey contends that many forms of 15th-century

painting, including the putto, responded to everyday

experience. "And everyday experience is something that's

lived in terms of the vernacular, not in terms of some

remote, classical past. The putto has a classical pedigree,

but a vernacular name and meaning. The spiritelli are very

deeply embedded in medieval and Renaissance physiological

concepts. They refer to how the body works, how it processes

sensations from outside. People in the 15th century had no

concept of the circulation of blood, so that [the] pulse,

which they could feel, was something generated by active

spirits in the body."

A central element of Dempsey's book is a new reading of

Botticelli's Mars and Venus. In the painting, a

lovely, serene Venus reclines beside an all-but-naked Mars,

who slumbers in what has most often been read as amorous,

even postcoital, bliss. Completing the composition are four

putti playing with Mars's lance and armor. Dempsey looks at

this classical subject and sees not bliss, but "a nightmare

of sexual obsession and domination, of a soul possessed and

tormented, not just by erotic fantasies, but by the demons

of Mars's own moral confusion." The putti, in this new

reading of the painting, are not classical allusions to

love, but vernacular representations of spirits of fright,

the torment of nightmares.

Dempsey notes how, after Donatello first employed the

device, it soon appeared throughout Renaissance art. "It

spread faster than e-mail. It was amazing how quickly this

was picked up. It was a successful and appealing invention,

a device that worked because everybody understood it.

"And they're cute." --DK

Health

Physician, Heal the

System

Future physicians know they will face hurdles in their

efforts to heal the sick: the high cost of prescription

drugs, the lack of adequate health care coverage, and

treatment barriers created by such issues as substance

abuse, domestic violence, and poverty.

A new student-generated course at the Hopkins

School of Medicine is meant to help first-year medical

students learn ways to go beyond their role as caregivers--

to work as political activists in addressing the underlying

weaknesses in providing medical care.

|

|

Illustration by Wesley

Bedrosian |

"We hope to get them exposed to all different ways that

a physician can be involved, not just in medicine, but more

broadly speaking in health care, and to do that in a way

that makes a difference," says Todd Varness, a fourth-year

Hopkins medical student who helped create the course. "We

want to catch them early when they have a lot of idealism. I

saw a lot of my classmates come in with idealism, but

unfortunately that can get beaten out of you over four

years."

"We hope to get them exposed to all different ways that

a physician can be involved, not just in medicine, but more

broadly speaking in health care, and to do that in a way

that makes a difference," says Todd Varness, a fourth-year

Hopkins medical student who helped create the course. "We

want to catch them early when they have a lot of idealism. I

saw a lot of my classmates come in with idealism, but

unfortunately that can get beaten out of you over four

years."

The Research-Based Health Activism class is being

taught for the first time this fall. Through guest speakers,

seminars, and case studies, a dozen medical students are

learning to do database searches, conduct surveys, and work

with the media. The goal: to develop a research question and

protocol to pursue during their years at Hopkins.

One project, for example, could include surveying

children for their responses to alcohol advertising, and

writing a policy paper. Another might entail finding out why

patients aren't making their doctor's appointments, and

lobbying City Hall for better public transportation.

Varness, who has a master's in public health and plans

to finish his medical degree in May, is helping manage the

course with Paul Jung, a Hopkins Robert Wood Johnson

Clinical Scholar, and Richard Humphrey, Hopkins associate

professor of medicine. The class is based on courses

developed by Peter Lurie, a former faculty member at the

University of Michigan and deputy director of Public

Citizen's Health Research Group. Lurie will be one of the

guest speakers.

Says Jung, "If anyone wants to get anything done in

health care they have to understand politics. You can be the

best diagnostician in the world, you could make a diagnosis

from 20 feet away, but it will not help your patients if

they can't get cheaper medicine." --JCS

Biomedicine

New Efforts to Engineer

Tissue Begin to Gel

One of the most intriguing bits of engineering in Clark

Hall, the newest building on the Homewood campus, is a

scaffold.

Not the wooden framework for the Georgian-style brick

building, but the concept of a tiny scaffold of

biodegradable polymers or other materials upon which

researchers hope to build knee cartilage, liver tissue, a

heart valve, or, someday, an entire beating human heart.

The three-story Clark Hall, which this fall started

housing faculty from Hopkins's recently launched Whitaker

Biomedical Engineering Institute, includes lab space for

researchers tackling a relatively new field of science:

tissue engineering. In particular, Hopkins scientists are

looking at the interaction between the body's cells and the

scaffold surfaces required for complex tissue to grow.

Jennifer Elisseeff and Kevin Yarema, both assistant

professors of biomedical

engineering in the Whiting School of Engineering, are

suitemates--106A and 106B. Elisseeff is working on new

biomaterials for scaffolds. Yarema considers himself a cell

engineer. As Yarema notes: "You have to make the scaffolding

more friendly to the cell or the cell more friendly to the

scaffolding."

|

Jennifer Elisseeff and Kevin Yarema in the lobby of the

new Clark Hall, below right.

Photo by Chris

Hartlove |

Tissue cells grown in a petri dish are usually little

more than a thin film. So building effective scaffolds--

often biodegradable materials that would melt away as cells

grow and divide--would allow the engineering of more complex

organs or body parts. The scaffold could be molded in the

shape of an ear, for example. In other advances, skin and

cartilage are already being grown on scaffolds in the lab,

and coral has been used as the internal structure on which

to rebuild a man's thumb.

Tissue cells grown in a petri dish are usually little

more than a thin film. So building effective scaffolds--

often biodegradable materials that would melt away as cells

grow and divide--would allow the engineering of more complex

organs or body parts. The scaffold could be molded in the

shape of an ear, for example. In other advances, skin and

cartilage are already being grown on scaffolds in the lab,

and coral has been used as the internal structure on which

to rebuild a man's thumb.

But questions among researchers at Hopkins and

elsewhere remain numerous: Which is the best surface on

which to grow skin or heart cells? How would the cells stick

to the surface and begin to divide? How would the body take

over, with a little help from chemical growth factors, and

create new tissue nurtured with blood vessels?

Elisseeff, building on her earlier PhD research at MIT,

is working on malleable scaffolds made up of cell-laced

polymer hydrogels. The viscous gels, which have been

described as a sort of "living glue," contain encapsulated

cells that act as seed cells for new tissue growth. The

hydrogel is hardened into a supportive scaffold through

exposure to light, a process known as

photopolymerization.

|

|

Hopkins biomedical engineers are looking at interaction

between the body's cells and the scaffold surfaces required

for complex tissue to grow. |

Doctors have already used polymer gels and

photopolymerization to create coatings for artificial

implants, to restore bone, and even for dental fillings. But

one hurdle looms: The polymer gels must be exposed to light

in an "open area," which means doctors are trying to implant

the self-hardening material during surgery. The result: Gels

exposed to certain temperatures harden too soon or in the

wrong shape.

Elisseeff, after speaking with doctors encountering

problems, theorized that photopolymerization could also work

through layers of skin. That method would allow a surgeon to

use arthroscopic surgery, injecting an unhardened hydrogel

directly into the location, such as a knee, to help build

new cartilage tissue. The less invasive method showed

success in studies with lab mice at MIT. "We want to be able

to give physicians more control to shine the light when they

want and where they want," she says. Among other research

goals at Hopkins, Elisseeff is testing ways to extract

components from human cartilage tissue to create new

biological-based hydrogels to build scaffolds even more

compatible with living tissue.

Yarema, meanwhile, is focused on changing the tissue

cells, "to make the cell work more compatibly with the

scaffold," he says. One of his thrusts, based on his

postdoctoral research at the University of California,

Berkeley, is exploring the molecular surface of the cell. He

has focused specifically on sialic acid, a sugar on the

surface of cells that's important in biological processes,

including brain development.

Yarema and his fellow researchers at Berkeley added a

variation of a different sugar, ManNAc, to cells in hopes of

altering the molecular structure of sialic acid on the

cells' surface, making the cells easier to target. When

processed through the cells' biological pathways, the

altered sugar did change sialic acid, introducing ketones,

or chemical groups not usually found on the cell's surface.

Yarema believes these new ketones could "provide a unique

chemical handle on the cell's surface" poised to accept a

targeted chemical link on the scaffold. At Hopkins, Yarema

will test other modified sugars and look for ways to make

the connection work in a way that could be used to build

tissue.

The cell-to-scaffolding interaction is especially

important when engineering new tissue from stem cells, the

undifferentiated cells found in fetal tissue or adult human

bone marrow. "We need to engineer surfaces that are optimum

for stem cells to grow," says Murray Sachs, Hopkins director

of the Whitaker BME Institute. "How do you create an

environment where cells can differentiate into nerve cells

or heart muscle cells or bone cells?"

The answers will likely come from various quarters.

Sachs, Elisseeff, and others point out that tissue

engineering is an edgy, interdisciplinary science. The

field, which came into existence only a decade ago, brings

together biologists, orthopedic surgeons, computer

scientists, plastic surgeons, neurologists, cardiologists,

stem cell researchers, and engineers who specialize in

fields ranging from materials science to chemical

engineering.

About a dozen Hopkins faculty are tackling research

questions along these lines, including Leslie Tung,

associate professor of biomedical engineering, whose work

focuses in part on developing engineered heart muscles that

contract, and Kam Leong, professor of biomedical

engineering, who is synthesizing new biodegradable polymers

that could be useful in scaffolds. Christopher Chen,

assistant professor of biomedical engineering, is delving

into cells and their micro-environment, analyzing how

cell-to-cell signaling and microfabricated surfaces

influence cell proliferation and death.

About a dozen Hopkins faculty are tackling research

questions along these lines, including Leslie Tung,

associate professor of biomedical engineering, whose work

focuses in part on developing engineered heart muscles that

contract, and Kam Leong, professor of biomedical

engineering, who is synthesizing new biodegradable polymers

that could be useful in scaffolds. Christopher Chen,

assistant professor of biomedical engineering, is delving

into cells and their micro-environment, analyzing how

cell-to-cell signaling and microfabricated surfaces

influence cell proliferation and death.

Potential applications for such tissue engineering

research hold out great promise: Perfect new skin grown for

burn victims, new inner ear cells generated to restore

hearing to the deaf, or nerve cells grown to reverse

paralysis. And patients needing organ transplantations

wouldn't be plagued by the scarce availability of donor

organs, or the problems of infection or durability linked to

artificial hearts and other organs made of metal, ceramics,

or Dacron. --JCS

Historic

Houses

A Palette for Life's

Lessons

During the early 1800s, needlework was a primary means of

educating girls in America: a hands-on way for them to learn

geography, history, French, English, arithmetic, and other

subjects. In Maryland and elsewhere, needlework also

provided a parlor room palette on which to teach lessons

about morality and domestic life.

At Hopkins's

Homewood House Museum, examples of such work are being

exhibited and discussed in a fall exhibit titled "Needles

and Threads: Women's Handiwork, Men's Craftsmanship." The

exhibit, which runs through November 25, also features

mahogany work tables and other furniture crafted by Maryland

cabinetmaker John Needles and his young male apprentices, as

well as English embroidery scissors, pincushions, sewing

boxes, and girls' needlework samplers.

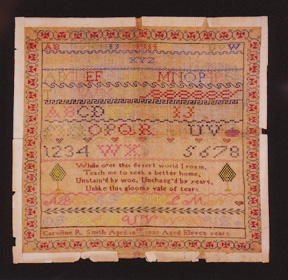

One vividly preserved 1832 example by 11-year-old

Caroline R. Smith of Maryland likely has never been

displayed before, curators believe. (Many samplers are faded

because vegetable dyes then used to color embroidery threads

are highly sensitive to light.) Smith's neatly wrought,

deeply colored sampler (shown at right) includes classically

inspired motifs such as waves and laurel leaves, as well as

a verse typical of the time period.

One vividly preserved 1832 example by 11-year-old

Caroline R. Smith of Maryland likely has never been

displayed before, curators believe. (Many samplers are faded

because vegetable dyes then used to color embroidery threads

are highly sensitive to light.) Smith's neatly wrought,

deeply colored sampler (shown at right) includes classically

inspired motifs such as waves and laurel leaves, as well as

a verse typical of the time period.

"Mourning embroideries became very popular," says

Catherine Rogers Arthur, curator of Homewood House. "It is a

sad reminder of how ever-present loss was in early

19th-century life. It was not uncommon for a girl of 11

years old to have lost siblings or a mother in childbirth.

It was very present in their minds. And they put a lot of

hope in the afterlife." --JCS

Alumni

Catching Up with Greg

Drozdek '95

Greg Drozdek '95 is once again uniting two worlds he knows

well: the New York streets and reaching out to children.

Drozdek was featured in our February 1995 issue in

"A Long Way from the

Old Neighborhood," which described his experiences as a

homeless 16-year-old in New York City. He managed to put

himself through Catholic high school and eventually talked

his way into Hopkins, where he played football and founded

the Hopkins Student-Athlete Mentoring Program.

Today, Drozdek is continuing to help at-risk kids

through the Stanton Street Settlement, a privately

supported, non-profit learning center he founded in 1999 for

children in New York's Lower East Side. He also teaches

English at Manhattan's La Salle Academy and is completing a

PhD in educational administration at New York University.

Drozdek patterned Stanton Street Settlement after the

first American settlement house, Jane Addams's Hull House,

which opened in Chicago in 1889. The idea, borrowed from

England, was to provide education and social services to the

urban poor. Drozdek had noticed an empty storefront, and in

what he describes as

Drozdek patterned Stanton Street Settlement after the

first American settlement house, Jane Addams's Hull House,

which opened in Chicago in 1889. The idea, borrowed from

England, was to provide education and social services to the

urban poor. Drozdek had noticed an empty storefront, and in

what he describes as

a "bells of St. Mary's moment," he conceived of a modern

settlement house to serve neighborhood immigrant kids.

He enlisted help from other Hopkins alumni--many now

serve on the settlement's board and as volunteers--and other

donors. The settlement

(

www.stantonstreet.org).

serves about 35 children, ages 4 to 13, providing

after-school tutoring, a chess program, field trips, and

cooking, computer, and fitness classes. Says Drozdek, "We're

offering the extra programs that public schools have been

forced to cut." --DK

In Memoriam

A Voice That Will Be

Missed

Peter W. Jusczyk, a Hopkins

psychology professor

who was an internationally regarded pioneer in the study of

infant language perception and speech development, died

August 23 while attending a scientific meeting in

California. He was 53.

Jusczyk's unexpected death stunned students and faculty

in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, where he was

known for the Infant Language Research Laboratory that he

operated with his wife and fellow Hopkins researcher, Ann

Marie Jusczyk. Through studies involving hundreds of babies,

he and his colleagues showed infants are able to recognize

and process sounds related to language at very young ages.

(See "The Origins of

Babble," Hopkins Magazine, February 1998.) In

1997 he published an influential book on the subject, The

Discovery of Spoken Language.

|

Peter Jusczyk with some young friends

Photo by Jay Van

Rensselaer |

"Peter was passionate about everything he did, either

in a professional context or for fun," says Greg Ball,

psychology professor at the Krieger School and a friend of

Jusczyk's. "I was always impressed by the breadth of his

intellect. His thinking was influenced by ideas and findings

from many fields, ranging from linguistics to neuroscience

or even engineering." Among the many professional honors

Jusczyk received was his election last year to the

prestigious Society of Experimental Psychologists.

"Peter was passionate about everything he did, either

in a professional context or for fun," says Greg Ball,

psychology professor at the Krieger School and a friend of

Jusczyk's. "I was always impressed by the breadth of his

intellect. His thinking was influenced by ideas and findings

from many fields, ranging from linguistics to neuroscience

or even engineering." Among the many professional honors

Jusczyk received was his election last year to the

prestigious Society of Experimental Psychologists.

In 1999, Jusczyk and colleague Ruth Tincoff presented

the first-ever evidence that infants as young as 6 months

can associate words with meanings. The words with meanings

were the crucial childhood words of "mama" and "dada."

"Most of the previous work on comprehension indicated

it was 8 or 10 months of age when kids started to attach

labels to particular objects," Jusczyk said at the time.

"The difference here is the words name important social

figures. This suggests that infants begin forming a lexicon

with sound patterns linked directly to socially significant

people, such as their parents."

Another aspect of Jusczyk's research focused on

determining when infants were able to distinguish between

sounds of their native language and other languages based on

common sound patterns in their native tongue. He showed that

this ability developed sometime between the sixth and the

ninth month of infancy. --Michael Purdy

Return to November 2001 Table

of Contents

Return to November 2001 Table

of Contents

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street |

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street |