|

|

JUNE 1999 CONTENTS

|

|

AUTHOR'S NOTEBOOK

|

|

You name the big bouts in boxing

and writer Phil Berger '64 has been there, to capture the

"trickerations" and the spectacle

|

Ringside Chronicles

By Dale Keiger

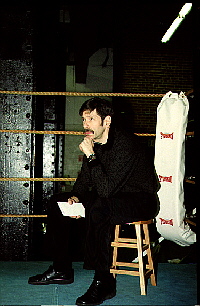

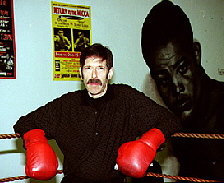

Photos by Teddy Blackburn

No. It has to be louder, much louder, and the syllables have to be drawn out, stretched like a rope through a turnbuckle.

Ladiiiiies aaaaand gennnnntlemennnnn....

Yeah, that's better. Though the man with the microphone is dressed in black tie, we're not in Carnegie Hall. The other guys in the spotlight go by names like Bonecrusher, El Torito, Iron Mike, Buster, Macho, Sugar Ray, and Marvelous Marvin. They come from hardscrabble circumstances in which hitting someone for pay represents one of their better options. They might earn $20 million for 91 seconds of work-- it's been done--but more likely they'll end up as what is known as a "tomato can." And no matter who they are, the instant multimillionaire or the tinned vegetable, they're likely at some point to become a victim of the trickerations of the fight game, to borrow a term coined by one of its more flamboyant promoters.

If you're a writer--and Phil Berger '64 is a pretty good one--the language of this arena, the boxing ring, is but one of its attractions. There are the characters, and the sheer spectacle. On a given night, you might witness a soft-spoken man of God losing a chunk of his ear to the canines and premolars of a convicted rapist. Your evening's entertainment might be promoted by a Talmudic scholar with a Harvard sheepskin on the wall, or by an equally successful loudmouth (Mr. Trickerations) who once served time for manslaughter. On the way to your seat you might brush sleeves with a real estate mogul, a starlet, a gambler with a hundred grand riding on the outcome, or a guy whose résumé includes "cut man" as a line item. A few seats over could be Muhammad Ali, deservedly known as The Greatest, or a large fellow who used to be called, accurately, the Bayonne Bleeder.

Boxing has been Phil Berger's fascination as a writer for more than 30 years. "It's just a very visceral experience when you see two great, well-conditioned athletes going at each other," he says. "There are people who are repulsed by it. I understand that. But it's kind of like your reaction to music. It either hits you as something that's exciting, or it doesn't. And for a writer it's just full of rich characters."

As a kid, Berger watched the Gillette Friday Night Fights ("Ladiiiiies aaaaand gennnnntlemennnnn....") on television. As a Hopkins liberal arts student he'd go to movie theaters in Baltimore for closed-circuit broadcasts of prizefights. As a writer, he spent seven years covering his favorite bloodsport for the genteel New York Times, and he has authored more than 15 books, including two novels, three ghosted autobiographies, several children's sports books, and volumes on boxing, basketball, and stand-up comedy. Not to mention, in his early days, magazine articles like "Coed Hookers."

At the beginning of March, Berger stares at the slush accumulating on the balcony of his apartment in Manhattan's East Village, counting the days before he flies to Hollywood. New Line Cinema is set to begin filming his screenplay, Price of Glory, starring Jimmy Smits, late of television's NYPD Blue, and Jon Seda of Homicide. Berger is more than ready. He wants to get the hell out of New York and spend some time around palm trees and a big-shot film crew.

"The day it begins shooting I'll be very happy," he says, "because I'll be getting what I've wanted."

He covered the big-time fights and fighters of the late 1980s:

Michael Spinks, Gerry Cooney, Hector Macho Camacho, Marvelous

Marvin Hagler, James Bonecrusher Smith, Sugar Ray Leonard, Bobby

Czyz, Buster Douglas, Larry Holmes. He wrote about other fight

people: promoters like Harvard-educated Bob Arum and

street-educated Don King, a former convict with wild standup hair

who delighted in making bombastic statements to the "boss

scribes" in the press about the "trickerations" of the fight

game; cornermen like Angelo Dundee, who trained nine world

champions, including Sugar Ray Leonard and Muhammad Ali;

characters out of a Damon Runyon story, like promoter Butch

Lewis, who liked to show up at big fights wearing a tuxedo,

complete with bow tie but no shirt; and hard-luck cases like Tony

"El Torito" Ayala, Vinnie Pazienza, and Leon Spinks, talented

fighters whose brief glory in the ring was eclipsed by their

misfortunes outside it. He wrote about Dave Jaco, an affable

single father ("a sweetheart-type guy," Berger recalls) who made

a thousand here, a thousand there as a "tomato can," a fighter

whose job, in Berger's phrase, was to be "a body for better men

to beat on." Berger delved into the treacherous and byzantine

business side of the sport: "Even if you're a good fighter, you

get beat up financially if you don't watch out, if you're

associated with the wrong sort of promoter or manager, a Don King

type, or King himself."

He covered the big-time fights and fighters of the late 1980s:

Michael Spinks, Gerry Cooney, Hector Macho Camacho, Marvelous

Marvin Hagler, James Bonecrusher Smith, Sugar Ray Leonard, Bobby

Czyz, Buster Douglas, Larry Holmes. He wrote about other fight

people: promoters like Harvard-educated Bob Arum and

street-educated Don King, a former convict with wild standup hair

who delighted in making bombastic statements to the "boss

scribes" in the press about the "trickerations" of the fight

game; cornermen like Angelo Dundee, who trained nine world

champions, including Sugar Ray Leonard and Muhammad Ali;

characters out of a Damon Runyon story, like promoter Butch

Lewis, who liked to show up at big fights wearing a tuxedo,

complete with bow tie but no shirt; and hard-luck cases like Tony

"El Torito" Ayala, Vinnie Pazienza, and Leon Spinks, talented

fighters whose brief glory in the ring was eclipsed by their

misfortunes outside it. He wrote about Dave Jaco, an affable

single father ("a sweetheart-type guy," Berger recalls) who made

a thousand here, a thousand there as a "tomato can," a fighter

whose job, in Berger's phrase, was to be "a body for better men

to beat on." Berger delved into the treacherous and byzantine

business side of the sport: "Even if you're a good fighter, you

get beat up financially if you don't watch out, if you're

associated with the wrong sort of promoter or manager, a Don King

type, or King himself."