|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Grassroots Guru

|

|

|

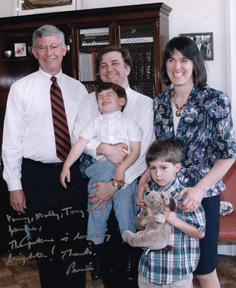

Opening Photo: Vinny DeMarco and Molly Mitchell,

with their sons, Jamie (left) and Tony, and Paz, the family

dog. Photo by John Davis |

When Vinny DeMarco arrived in Annapolis that April morning,

he thought he had a winner. It was the last day of the 2004

Maryland General Assembly session, and the bill his

organization, Maryland Citizens' Health Initiative (MCHI),

had been working to get passed was up for a vote. If House

Bill 1271 passed, about 76,000 Marylanders without health

insurance would get it, and many thousands more would have

access to free preventive care. The bill would eliminate

the HMO exemption to the 2 percent tax on premiums that all

other Maryland health insurance companies pay, and the

funds generated would be used to expand Medicaid. DeMarco's optimism is legendary — the Baltimore Sun once wrote that he "could find the bright side of an Internal Revenue Service audit" — but his sunny outlook on this day was well founded. The bill had been passed in the House two weeks earlier, the Senate version had changes DeMarco was pleased with, and he was confident of a majority support. DeMarco, MCHI's president, and the rest of the staff had been laying the groundwork for this vote for almost five years. They had originally put together a proposal called Health Care for All! The bill was a complex and ambitious plan to guarantee quality and affordable health care in Maryland that never made it past the Senate Finance or House Health and Government Operations Committee hearings in February. When that bill died, the Baltimore-based MCHI threw its support behind HB1271, a bill sponsored by Delegate John Hurson, chairman of the HGOC. On the day of the vote, DeMarco arrived early. He spent the day patrolling the halls outside the Senate chamber, catching senators when he could, answering questions when asked, but mostly waiting. When a Senate committee staffer called DeMarco two hours before the end of the session, he was floored. Despite his efforts, the bill had failed 24 to 22. "I was in shock for a while," says DeMarco. "I was in a daze. It's 10:30 at night, I've been there since 7 in the morning. I'm completely exhausted. It's raining out. And I just saw this work, all these people's hard work gone down the tubes — temporarily. And I just kept thinking that 70,000 people who don't have health care would have gotten it, and now aren't." It's hard to say exactly what happened. Maybe it was too much to expect the Senate to pass a tax increase in a year of budget deficits. Some people have speculated that the bill was the victim of political infighting. And Governor Robert Ehrlich — who is, legislatively speaking, one of the most powerful governors in the country — opposed the bill.

"Our goal this session was to pass the very big step that

this was, and then keep working on our plan," says DeMarco.

"The fact that it came so close was a combination of

extremely frustrating and good news for the future."  |

| Parris Glendening with DeMarco and family after signing the tobacco tax increase into law. "The future is looking brighter!" Glendening wrote. |

Vinny DeMarco, A&S '79, '81 (MA), is used to tough fights.

First it was gun control. In the late 1980s, he led a

successful effort to ban Saturday Night Specials in

Maryland, then fought off the National Rifle Association's

$7 million effort to overturn the ban through a referendum.

He successfully lobbied for several subsequent gun-control

measures, including the 1996 Maryland Gun Violence

Prevention Law, which limits the number of guns an

individual can purchase in the state to one per month.

Vinny DeMarco, A&S '79, '81 (MA), is used to tough fights.

First it was gun control. In the late 1980s, he led a

successful effort to ban Saturday Night Specials in

Maryland, then fought off the National Rifle Association's

$7 million effort to overturn the ban through a referendum.

He successfully lobbied for several subsequent gun-control

measures, including the 1996 Maryland Gun Violence

Prevention Law, which limits the number of guns an

individual can purchase in the state to one per month.In the '90s, it was tobacco. Studies show that higher prices discourage teenagers from smoking, so DeMarco worked closely with then-Governor Parris Glendening to increase the state's tobacco tax. "According to the data, a couple years later, 20,000 fewer kids smoked," says DeMarco. DeMarco's causes, and his tireless efforts in support of them, have made him a fixture in Maryland politics. Around Annapolis, he has built a reputation — as an eternal optimist, a relentless nudge, an affable guy who bears a jar of his Italian mother's tomato sauce when greeting politicians, a man whose heart is in the right place. "He has a chance to do good and save lives," says Eric Gally, MCHI's lobbyist. "And he likes doing it." Jen Hobbins, a member of MCHI's board, recalls her conversation with a fellow member in an elevator on the way to a meeting with DeMarco: "He turned to me and said, 'Now, which good thing does Vinny have us here for today?'" His latest cause is health care. And DeMarco, who friends have likened to the detective Columbo — a little rumpled and disorganized, but razor sharp when it comes to getting the job done — is bringing his well-tested method of campaigning to the effort. "He is a master of grassroots organization in Maryland," says Delegate Maggie McIntosh, who has known DeMarco since he was a student at Hopkins. "He has an idea, and the next thing you know, six months later, he has an office, a budget, and a thousand organizations signed on to help him." Not everyone supports DeMarco's causes — or his methods. But most recognize that he is effective.

"I have never met anybody in this process who had more

focus and energy on a single issue that Vinny does," says

Dennis McCoy, a government affairs attorney who counts the

tobacco company Philip Morris among his clients. "Sometimes

that focus and energy carry the day."  |

| DeMarco offers Vice President Al Gore a jar of his mother's tomato sauce. |

There are 44 million people without health care coverage in

the United States. In Maryland alone, close to 700,000

people have no health insurance whatsoever, and hundreds of

thousands of underinsured can't afford primary preventive

care. For them, sickness can mean missed work, crippling

hospital bills, sometimes even bankruptcy. By law, a

critically ill person can't be turned away from an

emergency room, so those who have health insurance

subsidize those who don't.

There are 44 million people without health care coverage in

the United States. In Maryland alone, close to 700,000

people have no health insurance whatsoever, and hundreds of

thousands of underinsured can't afford primary preventive

care. For them, sickness can mean missed work, crippling

hospital bills, sometimes even bankruptcy. By law, a

critically ill person can't be turned away from an

emergency room, so those who have health insurance

subsidize those who don't. This does not sit well with Baltimore City Health Commissioner Peter Beilenson, SPH '90 (MPH). "I frankly cannot believe that we continue to allow ourselves to be one of three major countries left in the world — Turkey and Mexico being the others — that do not have universal health coverage," Beilenson says. "Yet we're the wealthiest, most technologically advanced country in the world. It is simply unconscionable." In 1998, frustrated by the fact that even during an economic boom there were more Marylanders without health insurance than there had been a decade before, Beilenson wanted to do something about it. "It was very clear to me that so much of what we're doing in public health is filling in gaps or doing the band-aid approach to health care," he says. Anytime the city looks for funding — for drug treatment or cancer screening programs, for instance — it's to help the uninsured. "Why not go for the comprehensive approach?" he asks. When Beilenson began to get a group together to work on a plan and needed someone to head things up, he thought of DeMarco, whose tobacco tax campaign was nearly complete. "I knew he was about to be successful again and work himself out of a job," says Beilenson. As health commissioner, Beilenson had worked with DeMarco on the gun-control and tobacco tax efforts. DeMarco "seemed to have a very successful template for social change through the political process," Beilenson says. "He's very good at getting together these coalitions of community groups, along with working with a smart legislative proposal and picking the right legislators to carry the issue." When DeMarco took on the gun lobby in the late '80s, there hadn't been any significant gun-control legislation passed anywhere in the country in years. Yet, three years later, Maryland signed the Saturday Night Special Ban into law, and inspired other states to pass similar measures. "It was at the time the biggest defeat the NRA had suffered anywhere in the United States for a decade," says Bernie Horn, A&S '78, a classmate of DeMarco's from Hopkins who worked on the bill. "Vinny was one of the most famous opponents of the NRA. Individual NRA members knew and hated Vinny." When DeMarco turned his attention to Big Tobacco in the '90s, C. Fraser Smith declared in a Baltimore Sun column that the budget surplus at the time meant that a tobacco tax increase was "simply unthinkable." Yet, two years later, Glendening signed the increase into law. Health care would be the toughest fight yet. Though it is widely accepted that Maryland is facing a health care crisis, there are huge philosophical differences about what should be done. Finding an affordable solution would be a challenge. Once on board with MCHI, DeMarco set to work, getting funding, researching the issue, rallying support. Perhaps the signature element of a DeMarco campaign is his coalition-building. "I work with a lot of organizations like Vinny's all over the country and deal with executive directors who are trying to do as well as Vinny," says Horn, who is policy director for the Center for Policy Alternatives in Washington, D.C. "And nobody is as original, nobody comes up with so many new ways to organize." "Vinny is very good at going around and getting the disparate members of the community, and the groups that are interested in the issue, all together on the same page, in the same room, on the same bill," says MCHI lobbyist Gally. Early on in a campaign, before DeMarco even thinks about the Legislature, he and his staff begin holding community forums — asking questions, addressing concerns, and getting people to pledge their support. One of DeMarco's favorite groups to work with is the faith community. A Quaker, DeMarco is particularly good at getting religious groups to sign onto a campaign. "He's very persistent, he's very persuasive, he's kind of in your face until you begin to take notice of the issue," says Bishop Douglas I. Miles, executive director of the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance in Baltimore. The alliance, which has a long history of political and social action, was a natural fit. But DeMarco also has been able to bring into the fold faith organizations that traditionally haven't been political. The Health Care for All! coalition includes Christian, Muslim, and Jewish groups, among others. DeMarco, who as a consultant for the national organization Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids organized Faith United Against Tobacco, says the faith community is crucial to a campaign. These groups bring moral authority, as well as a lot of media attention. And, he says, "that's where the people are to mobilize." More than 150 community and religious groups signed on to support DeMarco's gun-control efforts; the tobacco tax had more than 350 supporters. MCHI's Health Care for All! proposal has more than 1,100 state and local organizations signed on. "As far as we know, it's the largest coalition in Maryland history," says Beilenson, who chairs its board.

When that kind of coalition kicks into action, politicians

can't help but pay attention. "I get flagged down in the

hallways of Annapolis, and [legislators] say, 'Tell him to

stop getting so many people to call. The phone's ringing

off the hook,'" says Gally. "We hear stories of legislators

getting 400, 500, 600 e-mails and phone calls. . . . These

are real people — these are real people who live in

the districts of the people who they're calling." |

| "The reality is that when you're successful at doing this kind of major issue reform, you're going to find your share of people who resent you for it," says Glenn Schneider. "And Vinny has his share of people." |

DeMarco worked with researchers at the Johns Hopkins

Bloomberg School of Public

Health, the University of Maryland, and Georgetown

University to create the Health Care for All! proposal they

would eventually take to Annapolis. Building on existing

private and public health insurance systems, the plan would

require businesses to offer their employees affordable

health care coverage (those who didn't would be charged a

payroll assessment). The plan would also expand Medicaid

and set up a quasi-public program, MdCares, for those who

aren't otherwise covered. The plan carries a price tag of

about $665 million, which would be funded by a cigarette

tax increase, sliding-scale premiums for moderate-income

adults, penalty taxes on non-participating businesses and

individuals, and by maximizing federal matching funds. Though Johns Hopkins didn't take a position on the plan as an institution, the dean of the School of Public Health, Alfred Sommer, SPH '73, endorsed the Health Care for All! proposal. And when it came time to announce it, he offered space at the school for the press conference. "[DeMarco] captures people who think they're smart by making them feel like they are the brains behind the operation. He takes no credit for anything himself; he props these other people up in front of the camera so they feel good about it," says Sommer. "And I know this well because that's exactly what he's done with me."

Of course, not everyone supports the plan, especially the

business community. Robert O. C. "Rocky" Worcester, SPSBE

'72, A&S '73 (MA), president of Maryland Business for

Responsive Government (MBRG), argues that the plan will

actually encourage businesses to drop their health care

plans and pay the more affordable payroll tax instead,

thereby spelling the end of the private health insurance

industry in Maryland. "We want to address the problems

without destroying the system that provides insurance for

88 percent of the population, because 88 percent are

getting the best health coverage in the world," he says.

(According to DeMarco, the plan includes safeguards that

would prevent businesses from discontinuing coverage.) |

| DeMarco (in plaid) banned smoking from the City Council offices as "mayor for a day" in high school. |

Opponents also argue that the proposal makes businesses

— particularly small businesses — foot the

bill. "The small business community believes, yes, rising

health care costs are a major issue that needs to be

addressed," says Ellen Valentino of the National Federation

of Independent Business. "But establishing a government-run

system funded on the backs of small business is not the

solution."

Opponents also argue that the proposal makes businesses

— particularly small businesses — foot the

bill. "The small business community believes, yes, rising

health care costs are a major issue that needs to be

addressed," says Ellen Valentino of the National Federation

of Independent Business. "But establishing a government-run

system funded on the backs of small business is not the

solution."DeMarco is relentless in the face of such opposition. And he's pretty insistent when it comes to politicians as well. Though MCHI doesn't endorse candidates, through the group's affiliated 501(c)(4) (called Maryland Citizens' Health Initiative Inc.), DeMarco does encourage all those running for office to sign a pledge of support. And the coalition is very aggressive in letting voters know which candidates support or oppose an issue — holding press conferences, writing letters to the editor, and dogging candidates who haven't signed. DeMarco's opponents say that he can take his methods too far — that his practice of having legislators pledge support to a cause, as opposed to a specific bill, is unfair. "Until you actually see the bill," says Dennis McCoy, "you really can't say that you'll vote for that bill even though you may support the concept." He also has been criticized for going on the attack after a vote. In 1999, after six Republicans filibustered to stop the cigarette tax, DeMarco created radio ads that skewered the candidates for "choosing sides" against kids. The ad received plenty of criticism — especially for only targeting the Republican filibusterers and not naming those Democrats who voted against the bill — and DeMarco was accused of being a "partisan mouthpiece for the Democrats." "The only people on those ads were the people who stood up and yapped," counters DeMarco, whose voice still carries traces of his New Jersey childhood. "If Democrats had done it, they would have been on the ad." Glenn Schneider, MCHI's executive director, says this just goes with the territory. "The reality is that when you're successful at doing this kind of major issue reform, you're going to find your share of people who resent you for it, and Vinny has his share of people," says Schneider. "But more so than that, he's got a legion of people who love him and his methods and his approach to this kind of work."

Jamie DeMarco, 11, is singing the title song from Man of La Mancha. We're in Donna's coffee bar in Charles Village, having just finished breakfast with his dad, Vinny, and his mom, Molly Mitchell. (Brother Tony, 14, is away at camp.) As most of the restaurant's patrons quiet down to listen, Jamie, with his father's encouragement, offers an enthusiastic rendition:

I am I, Don Quixote,"Don Quixote is very symbolic for us. We love Man of La Mancha," DeMarco says with a grin. Jamie and his father, who admits to sometimes feeling like he's tilting at windmills, have listened to the Cervantes book on tape, watched the movie, and listened to the music. "It's very inspiring, isn't it Jamie?" says DeMarco. Mitchell adds, "To see things the way they could be and not just the way they are?" This may be the heart of what drives DeMarco. Born in Italy in 1957, DeMarco came to the United States with his family when he was 4 years old. They settled in New Jersey, where they ran a dry cleaning business, and DeMarco became a U.S. citizen at age 11. One of four siblings, he has a very close, supportive family. (His mother and sister were present the first time he argued a case in court, and, to the judge's surprise, gave DeMarco a standing ovation. His father still cuts his hair.) As a kid, DeMarco loved reading about history and politics; he especially liked biographies of people like Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, JFK, Eleanor Roosevelt. "From when I was very young, people who would take on hard battles to make society better always fascinated me." As a teenager, he worked on political campaigns and, as "mayor for a day" during his senior year in high school, banned smoking from the Hazlet City Council offices. When DeMarco came to Hopkins in 1974 to study political science, he became active in the Young Democrats, joined the debate team, and helped urban kids with reading and math as part of the Tutorial Project. He was also "breathtakingly smart," says Horn. "Classes at Hopkins were a breeze for him, and all of his friends just wanted to strangle him because it was so easy for him — or seemed to be so easy for him — to excel at Hopkins when we were struggling to figure out what the professors were talking about."

One of the classes they took together was Contemporary

Political Theory with Richard Flathman. "Of a class of

about 30, about 29 of us didn't know what was going on,"

says Horn. "Professor Flathman and Vinny held a dialogue

for the length of the class, then we would come back the

next week and they'd hold another dialogue." |

|

Jen Hobbins, Glenn Schneider, and DeMarco do their part

to "Bridge the Gap." Photo by Stephan Lieske |

After his junior year, DeMarco left for Columbia Law School

as part of Hopkins' Advanced Interdisciplinary Legal

Education Program. He earned his JD (though barely —

working on Ted Kennedy's presidential campaign instead of

studying, he squeaked by his exams). Then he returned to

Hopkins for a graduate degree in

American history, turning down a very lucrative offer

from a major Washington, D.C., law firm to do so.

After his junior year, DeMarco left for Columbia Law School

as part of Hopkins' Advanced Interdisciplinary Legal

Education Program. He earned his JD (though barely —

working on Ted Kennedy's presidential campaign instead of

studying, he squeaked by his exams). Then he returned to

Hopkins for a graduate degree in

American history, turning down a very lucrative offer

from a major Washington, D.C., law firm to do so. After getting his master's degree, DeMarco went to work in the Maryland Attorney General's Office and eventually became an assistant attorney general working on licensing regulation. When the AG, Stephen H. Sachs, ran for governor, DeMarco quit his job to help with the campaign. That's when he came across the name Molly Mitchell on a volunteer card. When he called her about attending a campaign event, he recalls, "I just loved her voice. Strange but true. A great, great voice." After the event, says DeMarco, "I spent the next hour asking about 10 people there, including Molly, to have pizza afterwards and hoping the other nine would say no." They did. DeMarco and Mitchell were married in 1987, when he was 30. Tony was born in 1990, and Jamie was born on Election Day 1992. "I think that he's most proud of his title as a father and a husband," says Schneider. "I've never seen him miss his sons' baseball games or recitals." Tony wants to be a major league baseball player. Jamie, who is more artistic, would like to be an actor. Both seem to have picked up some of their father's zeal for causes. Jamie, who hates Wal-Mart because, he says, it uses child labor overseas and doesn't make health care coverage affordable for its employees, once asked a delegate visiting his school whether her bill could be filibustered. And during a Cub Scout tour of Annapolis, Tony grilled their guide, another delegate, about where he stood on the tobacco issue.

As DeMarco has carried on his work — as an assistant

attorney general, as a lobbyist, as the head of one

non-profit or another — it is his family that has

sustained him, he says. They've inspired him as well. Says

DeMarco, "I always think about the kind of world Tony and

Jamie will grow up in."  |

|

Delegate James Hubbard and DeMarco before the

march. Photo by Stephan Lieske |

Bad bills take 90 days; good bills take two or three

years," says Delegate James W. Hubbard, who, along with

Senator Nathaniel J. McFadden, sponsored the failed Health

Care for All! bill. "Grassroots always wins, it just takes

longer."

Bad bills take 90 days; good bills take two or three

years," says Delegate James W. Hubbard, who, along with

Senator Nathaniel J. McFadden, sponsored the failed Health

Care for All! bill. "Grassroots always wins, it just takes

longer."It's a glorious Saturday morning in June, and Hubbard — along with DeMarco, Beilenson, Schneider, and about 300 other people — has come to Baltimore's Hanover Street bridge for a grassroots event called "Bridging the Gap to Health Care." Across the country, according to the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which organized the event, tens of thousands of people are crossing bridges in similar walks meant to call attention to the 44 million Americans without access to health care. The crowd in Baltimore isn't huge, but it's in high spirits. "A powerful grassroots coalition can make a difference," says DeMarco. "What happened this session, the fact that this health care expansion came so close after being nowhere for so many years, is a testament to the power of this coalition." Now that coalition is making plans for the 2005 legislative session. They are holding so-called "listening meetings" to decide whether to introduce the Health Care for All! bill. They are working with Maryland senior groups to highlight problems with the recently enacted Medicare Prescription Drug law, encouraging the Maryland General Assembly to pass legislation that would allow the state to negotiate cheaper drug prices with pharmaceutical companies. They are working with hospitals around the state to make sure that patients know about the financial assistance policies that are already in place. And they hope to launch a campaign this fall that would educate doctors and other health care providers about what commonly prescribed drugs actually cost. All these steps are in the right direction, says DeMarco, but they're not the end. "We've got to keep the goal of health care for all. That's got to happen." Is he aiming too high this time? The people who have watched him and worked with him through the years don't think so. "That's the fight he thinks needs to be fought," says Horn. "If he's not going to take on the biggest obstacles to progress, who will?" Catherine Pierre is the magazine's associate editor. |

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231

The Johns Hopkins Magazine |

901 S. Bond St. | Suite 540 |

Baltimore, MD 21231Phone 443-287-9900 | Fax 443-287-9898 | E-mail jhmagazine@jhu.edu |

|