|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Cold Comfort

Cold ComfortThey thought they were ready for any challenge. But the Johns Hopkins students on a winter camping expedition in the Adirondacks found their resolve and their leadership skills tested -- at minus 20 Fahrenheit. By Robert Roper

|

|

| Opening photo by Matt "Spinner" Allen |

The mission statement of the Hopkins outdoor program puts

the matter baldly. "We desire to push people out of their

comfort zone," it says, "so they can see themselves ... in

new ways." The question then becomes, how big is your

comfort zone? Would you be happy sleeping for a couple of

nights in a tent? How about a tent in the snow? How about a

tent in the snow in zero-degree weather? How about a tent

in the snow for 10 days with a low of minus 30, wind chill

not included? How about a tent in the snow and never quite getting warm all day, needing to rest but afraid to stop moving because then the freeze sets in? Your feet and hands losing all feeling, the frostbite starting on your face? That's a different idea of a comfort zone, a more special one, and this January, those questions took on real meaning for a group of Johns Hopkins students. They had set out for two weeks of winter camping in the Adirondacks, prepared for cold and snow and all the challenges entailed in that, but they were destined to encounter truly serious cold, Alaska-style cold, near-historic lows for the High Peaks region of upper New York state. The whole literature of survival in the winter wilderness, from Jack London's "To Build a Fire" to Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air, suddenly seemed strangely relevant. The trip, organized as part of HOLT (Hopkins Outdoor Leadership Training), placed the students in a situation where "their decisions had real consequences," according to Phil Zook Friesen, the university outdoor coordinator and someone well-acquainted with the challenges of backwoods winter travel. A former Sierra mountain guide, Friesen has been developing a cadre of student leaders at Hopkins, men and women trained in specific skills -- rock climbing, backpacking, white water kayaking -- and with tested decision-making abilities. His goal is to be able to offer an ever richer variety of outdoor activities for the Hopkins community, in an atmosphere of safety and fun.

|

|

"Frozen Circus"

included Eric Schenfeld (foreground) and

Jon Haslanger, Glenn Wolfe, Katie Francis, Justin Plaum,

Sarah Spriet, Liz Pazdernik, and Spinner

Allen. Photo by Kate Francis |

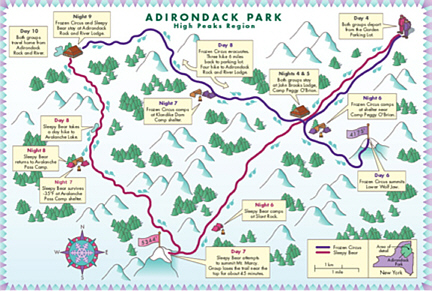

Among the 14 students on the January expedition, several

were hoping to become student leaders in this summer's

Pre-Orientation Programs, which offer six- to eight-day

wilderness trips for incoming freshmen. Friesen divided his

group into two smaller squads, one called "Sleepy Bear" and

the other, aptly, "Frozen Circus." The plan: to travel from

Baltimore to upstate New York on the first day, then to

spend Days 2 and 3 at the Rock and River Lodge, testing

gear and making preparations to set out on Day 4. Both

groups would spend the nights of Days 4 and 5 at Camp Peggy

O'Brian, then would separate and take different trails into

the back country (see map). Each of the teams worked out an

itinerary through the wilderness, and, so that everyone

hoping to become a student leader could gain experience,

the directing duties were rotated daily.

Among the 14 students on the January expedition, several

were hoping to become student leaders in this summer's

Pre-Orientation Programs, which offer six- to eight-day

wilderness trips for incoming freshmen. Friesen divided his

group into two smaller squads, one called "Sleepy Bear" and

the other, aptly, "Frozen Circus." The plan: to travel from

Baltimore to upstate New York on the first day, then to

spend Days 2 and 3 at the Rock and River Lodge, testing

gear and making preparations to set out on Day 4. Both

groups would spend the nights of Days 4 and 5 at Camp Peggy

O'Brian, then would separate and take different trails into

the back country (see map). Each of the teams worked out an

itinerary through the wilderness, and, so that everyone

hoping to become a student leader could gain experience,

the directing duties were rotated daily.One of the leader candidates, Liz Pazdernik, a graduate student in geography and environmental engineering, found herself in charge of Frozen Circus on Day 8, a day of truly bitter cold -- minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit. "This was my first true backpacking trip," Pazdernik says, "and maybe it was crazy to be doing that in the Adirondacks, in January, but anyhow, there I was. It was our second night out, and the temperatures had plummeted. You immediately felt your fingers and your feet freezing.... All you could think of was the cold, nothing but that. And in that state of mind you had to decide if your team should push on or evacuate. Basically, what in the world we should do. "Among our group, I was probably the coldest," she adds. "My co-leader went around to everybody and explained that we were bad off, really pretty bad off ... that I hadn't been warm in over 24 hours. Before conditions had become that severe, it had been easy to tinker around being leaders and decision-makers, but once it got that extreme, you didn't want to eat, you didn't want to drink, all you could think of was how cold you were."

|

|

"Sleepy Bear": Charles Reyner, Emily Kumpel, Jessica Richmond, Ayla Turnquist; (bottom, l to r) Howard Change, Phil Friesen, Kevin Pear. Not pictured: Sean Heffernan, Katy Juhaszova. Photo by Sarah Spriet |

After some discussion, the group decided to send four

members west, toward a heated lodge at a lower elevation.

Here they could recuperate in some comfort, while the three

other members of the group snowshoed six miles in the other

direction, their goal being to recover the group's rented

vehicles, which had been left at the trailhead, then drive

around to the lodge on paved roads. This decision allowed

the team members who were suffering most to get immediate

relief, although at the cost of abandoning the group's

mountaineering objectives for the day (they had been hoping

to climb Yard Mountain and Big Slide Mountain).

After some discussion, the group decided to send four

members west, toward a heated lodge at a lower elevation.

Here they could recuperate in some comfort, while the three

other members of the group snowshoed six miles in the other

direction, their goal being to recover the group's rented

vehicles, which had been left at the trailhead, then drive

around to the lodge on paved roads. This decision allowed

the team members who were suffering most to get immediate

relief, although at the cost of abandoning the group's

mountaineering objectives for the day (they had been hoping

to climb Yard Mountain and Big Slide Mountain)."There was a dual purpose to everything," Pazdernik says, referring to the training in decision-making. "There was the physical encounter with the conditions, unbelievably harsh, and then also this thoughtful guided training in how to make a smart call in the wilderness. You were encountering your core fears, dealing with elemental worries like frostbite and how do I ever get warm again, and meanwhile undergoing this sophisticated process, this exercise in interpersonal complexities." The leader candidates, although given considerable autonomy, were supervised at all times by Friesen and by six instructors who had been trained by Friesen and others. Experiential education, the pedagogy that underlies programs like HOLT and which owes a debt to Outward Bound and similar movements, posits personal growth as a dependable outcome of serious outdoor adventure. But any professionally run program of this kind will be full of fail-safe measures, backup personnel, and thoughtful plans for dealing with all contingencies. The trick is to devise genuine encounters with wilderness conditions that are serious as well as fun, that call on outdoor skills in a consequential way, but in an environment of carefully managed risk. Friesen, who has been working in programs of this kind for eight years, is a technical rock climber and a mountaineer. He has a warm, easy manner that turns even stern encounters with harsh conditions into exercises in relaxation: No, this is not about proving your manhood or womanhood, not about grimly holding on to the death, but rather about deep play, about mastering skills that can free you in the wilderness and also in life. His goal in developing student leaders is to build a staff at Hopkins capable of leading more trips, but even more to equip students to deal with challenges of any sort. The aim is a deeper enjoyment, a fuller immersion in a difficult world -- mindfulness and adventure-readiness.

Follow this link to a larger version of this map. The High Peaks region -- the area that contains all the Adirondack summits over 4,000 feet -- sees very little traffic in the dead of winter. (Perhaps the reason is that, as the Adirondack Mountain Club guidebook says, "the … region presents an abundance of extremely steep terrain as well as exposed alpine environments with the potential for arctic weather conditions.") For Eric Schenfeld, encountering the cold was really the point of the whole adventure. "I'd never slept out in winter," he says, "and I figured I could either do it now, while I'm at Hopkins, or pay Outward Bound or somebody like that a lot of money later." On the coldest mornings, "I woke up with no feeling in my feet," says Schenfeld. "I rubbed them for a long time and the only reason I knew that they were my feet, not blocks of wood, was that I was looking at them." Schenfeld was in the same group, Frozen Circus, as Liz Pazdernik. On Day 6, the team had climbed Lower Wolfjaw Mountain (4,175 feet), then had hiked to an open-sided shelter along Klondike Brook. That night was probably the coldest 12-hour period of the trip. (It was also the prelude to the decision, taken by Pazdernik and others, to split Circus and evacuate to Rock and River Lodge.) At around 8:30 a.m. the next morning, as they rubbed their feet and tried to thaw their boots, which had frozen solid despite being kept inside the tent, the temperature was about minus 20 (presumably, it had been at least 10 degrees colder during the night). Schenfeld was eager to push on, to try to snowshoe energetically all day, because, as he explains, "That's the only time I was really warm, really comfortably warm, when we were out hiking with full packs on. The nights weren't really restful ... you're in your sleeping bag for a long time, and it's supposed to be the warmest time of day for you, the time when you can recuperate. But it wasn't like that. Even if you took a hot-water bottle into your sleeping bag with you ... one person's hot-water bottle froze solid and broke inside the sleeping bag."

|

|

Both groups, led by Friesen, started and ended their

winter backpacing adventure at the Adirondack Rock and

River Lodge. Photo by Sarah Spriet |

The travelers ate well -- hearty, carbohydrate-rich food

cooked on portable stoves -- and there was a lot of

horseplay and camaraderie on the trail. But at the end of

the day, no matter how much good feeling and enjoyment had

been generated, there were those nighttime hours to be

passed in the bone-chilling cold.

The travelers ate well -- hearty, carbohydrate-rich food

cooked on portable stoves -- and there was a lot of

horseplay and camaraderie on the trail. But at the end of

the day, no matter how much good feeling and enjoyment had

been generated, there were those nighttime hours to be

passed in the bone-chilling cold.In retrospect, Friesen, who attended to both teams but traveled mostly with Sleepy Bear, thinks that Frozen Circus may have suffered more than Sleepy Bear because, on the day before the coldest night, they had snowshoed less far and thus had warmed up less thoroughly. In contrast, Sleepy Bear had gotten seriously warmed up trying to climb Mount Marcy, the tallest peak in the Adirondacks (5,344 feet). "In the process, we lost the trail because of blowing snow and other factors," says Friesen. "We were up in elevation, and the leader of the day lost a little control, as almost anybody would.... We spent about 45 minutes up around treeline, among the low shrubs and snow, searching for the trail and not finding it. At last, one of the students stumbled on it. It was now past noon and the temperature was minus 10, minus 20 with the wind chill.... We got up pretty high, I'd say, but couldn't quite make the summit, then headed north, toward Avalanche Pass, toward the lean-to we knew was there."

|

|

Katie Francis Photo by Matt "Spinner" Allen |

Friesen put some of the students into sleeping bags

immediately to warm them up and stave off hypothermia.

Several days earlier, Friesen had written in his private

journal: "Our first day in the field is drawing to a close

and it is brutally cold.... Hiking was not too bad, but ...

the cold was almost unbearable." And now, it was colder

than that, much colder. At Saranac Lake, some 25 miles

away, the recorded low was minus 31, and Friesen was fairly

sure that it had been even colder where his group was,

possibly minus 40 or below. As Friesen further noted in his

journal, "This course has been tough. One of the toughest

on me," because of his concern for his students, his wish

to deliver a stellar experience for everyone -- successful

ascents of winter mountains, fun times on the trail, warm

moments in the tents, lots of learning and growing and

maturing in the grip of nature. And here was nature, biting

back. Hard. "We have a beginner winter backpacking

course," he wrote, "and the temperatures could be

life-threatening if anything goes wrong.... Is this the

best way to teach leadership?" he wondered. "Is this course

accomplishing what it needs to or should?"

Friesen put some of the students into sleeping bags

immediately to warm them up and stave off hypothermia.

Several days earlier, Friesen had written in his private

journal: "Our first day in the field is drawing to a close

and it is brutally cold.... Hiking was not too bad, but ...

the cold was almost unbearable." And now, it was colder

than that, much colder. At Saranac Lake, some 25 miles

away, the recorded low was minus 31, and Friesen was fairly

sure that it had been even colder where his group was,

possibly minus 40 or below. As Friesen further noted in his

journal, "This course has been tough. One of the toughest

on me," because of his concern for his students, his wish

to deliver a stellar experience for everyone -- successful

ascents of winter mountains, fun times on the trail, warm

moments in the tents, lots of learning and growing and

maturing in the grip of nature. And here was nature, biting

back. Hard. "We have a beginner winter backpacking

course," he wrote, "and the temperatures could be

life-threatening if anything goes wrong.... Is this the

best way to teach leadership?" he wondered. "Is this course

accomplishing what it needs to or should?"On the day after Mount Marcy, Sleepy Bear remained in their sleeping bags until after 11 a.m. Then around 1 p.m., despite continued bitter cold, the team roused itself and snowshoed over Avalanche Pass and out onto frozen Avalanche Lake. The day, though severely cold, was brilliantly beautiful. Steep cliffs rise up on either side of Avalanche Lake, which occupies a cleft in the mountains, and in those surroundings, "Everyone just got lifted," says Howard Chang, one of Friesen's student instructors. "Just to be out and alive there was gorgeous. People had been bummed about not getting to the summit the day before, but this was an answer to that, a beautiful answer. It was spectacular and it will always be one of my greatest outdoor moments."

|

|

The picturesque view from the rear of the

lodge (above). Photo by Matt "Spinner" Allen |

For Liz Pazdernik and the other members of Frozen Circus,

the lodge had felt good, very good, after the nights out in

the open, nights of frozen boots, fear of frostbite, and

five people jammed uncomfortably in a four-man tent. But

now, a second crisis in decision-making arose. Should they

stay where they were, comfortably indoors, or instead

venture out again, prove their mountaineering mettle? Most

of the students did want to go out again: The program as

originally designed called for another foray into the High

Peaks, this time without any instructors along, the

students keeping in touch with Friesen and the other staff

only by radio. Then, when Sleepy Bear also arrived at the

lodge, Friesen and his group joined the ongoing discussion.

Friesen and the instructors asked the students to spell out

the risks involved in going out again: What would it mean

to go to their "breaking point," Friesen asked, in

continued sub-minus 20-degree weather? What if somebody

suffered serious frostbite? How did you justify permanent

injury, possibly a friend's loss of fingers or toes, in the

name of your "personal search for limits"? All the talk of

the ethics of risk and adventure now became bracingly real.

(On those same days in mid-January, a group from Dartmouth

College had to litter out a participant from the same

region of the Adirondack High Peaks -- the point, as

Friesen's students came to realize, was that any

unexpected development could become life-threatening in

such cold.)

For Liz Pazdernik and the other members of Frozen Circus,

the lodge had felt good, very good, after the nights out in

the open, nights of frozen boots, fear of frostbite, and

five people jammed uncomfortably in a four-man tent. But

now, a second crisis in decision-making arose. Should they

stay where they were, comfortably indoors, or instead

venture out again, prove their mountaineering mettle? Most

of the students did want to go out again: The program as

originally designed called for another foray into the High

Peaks, this time without any instructors along, the

students keeping in touch with Friesen and the other staff

only by radio. Then, when Sleepy Bear also arrived at the

lodge, Friesen and his group joined the ongoing discussion.

Friesen and the instructors asked the students to spell out

the risks involved in going out again: What would it mean

to go to their "breaking point," Friesen asked, in

continued sub-minus 20-degree weather? What if somebody

suffered serious frostbite? How did you justify permanent

injury, possibly a friend's loss of fingers or toes, in the

name of your "personal search for limits"? All the talk of

the ethics of risk and adventure now became bracingly real.

(On those same days in mid-January, a group from Dartmouth

College had to litter out a participant from the same

region of the Adirondack High Peaks -- the point, as

Friesen's students came to realize, was that any

unexpected development could become life-threatening in

such cold.)Reluctantly -- but with a lot of good discussion and "process" -- the group at last decided to cut the trip short. It would not be 14 days long, it would only be 10 days. They consoled themselves with the promise, however, of a session of ice climbing instruction in nearby Keene Valley, where, as it happened, the yearly Adirondack Mountain Festival was under way. But the chief ice climbing guide there, fearing frostbite in weather expected to be minus 12 or below, said no: In such conditions, the ice was too brittle and might shatter from the blow of an ice ax. Thus, a disappointing winter trip. Except that no one was disappointed.

|

|

After making the decision to evacuate, Frozen Circus

heads back to the Adirondack Rock and River

Lodge. Photo by Matt "Spinner" Allen |

"No, it was one of my best outdoor times," Howard Chang

says, "and I've been backpacking most of my life. I was

even an Eagle Scout. If the purpose was outdoor leadership

training, then this was beautifully designed.... Everyone

was definitely pushed to their limit, but no one went over

the limit, and that was because of the careful process.

Yeah, and it was fun, too. It was good to suffer!"

"No, it was one of my best outdoor times," Howard Chang

says, "and I've been backpacking most of my life. I was

even an Eagle Scout. If the purpose was outdoor leadership

training, then this was beautifully designed.... Everyone

was definitely pushed to their limit, but no one went over

the limit, and that was because of the careful process.

Yeah, and it was fun, too. It was good to suffer!"Katy Juhaszova, a student participant who had never done this kind of camping, says that she "loved the opportunity to see things that I had never seen and really push myself physically and mentally -- to get myself out of my comfort zone and my routine. I came back so refreshed and awakened," she adds. "For that, it was invaluable. Also meeting other outdoors-oriented people from Hopkins, getting a better idea of what was out there for me to get involved in." And Emily Kumpel, one of the students hoping to become a Pre-Orientation leader: "I thought there was an excellent combination of outdoor skills, leadership training, and group development. I especially liked the chance to bond with the group," she says. "At first I thought having leaders of the day was completely unfair, as I didn't feel I could show my leadership when I was so unsure of what I was doing. But as the course went on I realized what a true test of leadership that was and how essential the process is to learning. Leading when I had no idea what was going on ... became my favorite part of the course."

|

|

The view from Lower Wolfjaw. Photo by Matt "Spinner" Allen |

And Liz Pazdernik, who suffered so much from the cold, who

had to take the reins of leadership when she felt least up

to doing so: "I wouldn't take back a moment of it.... I now

know what it feels like to live outside in zero- to minus

30-degree weather," she says. "I'm now not worried about

hiking for a few miles with a heavy pack, and I know how to

find my way around the woods with a map and compass…. Since

being back I have a new, more lasting sense of

confidence....

And Liz Pazdernik, who suffered so much from the cold, who

had to take the reins of leadership when she felt least up

to doing so: "I wouldn't take back a moment of it.... I now

know what it feels like to live outside in zero- to minus

30-degree weather," she says. "I'm now not worried about

hiking for a few miles with a heavy pack, and I know how to

find my way around the woods with a map and compass…. Since

being back I have a new, more lasting sense of

confidence...."I will never forget what it felt like to face the bottom of my strength -- to face all of my anxieties at once, particularly the fear of failure. I am already preparing myself for more trips. The next thing will be rock climbing.... I've committed myself to getting trained and certified as a rock climbing leader this spring. "Ah," she says, "the glow of a successful experience!" Robert Roper, a visiting associate professor in the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins, is the author of Fatal Mountaineer: The High Altitude Life and Death of Willi Unsoeld, American Himalayan Legend. Last fall, Roper was awarded the 2002 Boardman Tasker Prize, an honor given each year by the British Alpine Club for an outstanding contribution to mountain literature. |

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street |

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street | Suite 100 | Baltimore, Maryland 21218 | Phone 410.516.7645 | Fax 410.516.5251 |

|