|

|

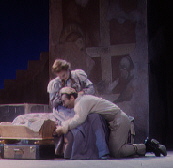

Philip (Taylor Armstrong) greets the

prima donna (Jae Eun Shin).

|

|

As they got deep into the production, Brunyate expressed regret

that he and Weiser hadn't taken a few more chances and written

something edgier, more modern. His narrative and staging are

mostly straightforward and realistic, and Weiser's score, though

it has its dissonant moments, is achingly beautiful and lyrical

in ways that have gone out of fashion with composers, though not

with audiences. But it's precisely this cut against the grain

that elevates Weiser's accomplishment. He has explored the

boundary between the melodic lushness of the 19th and early 20th

centuries and the dissonance of the last 50 years, and forged

something that seduces the heart but never stops surprising the

mind.

Weiser smiles a bit ruefully and says, "As a 20th-century

composer, you worry when you hear people say, 'It's so lyrical.'

But that didn't bother me with this project. What do I have to

prove?"

During one of the final rehearsals, Weiser's wife, Elizabeth, sat

beside him holding his hand. At the end of Caroline's beautiful

aria, she brought his hand to her lips and kissed it. Later in

the evening, Brunyate leaned over to Weiser, squeezed his

shoulder, and said, "This is the real thing."

Act 2, Scene 2

Opera within opera: Philip, Harriet, and Caroline attend a

village performance of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermore.

During the lead-in music, the cast backstage sings sections of

the Donizetti, including a bit of Lucia's mad scene in which the

coloratura must hit an E-flat above high C.

This has been one of those moments that everyone stopped to

listen for in rehearsal. During one of the first run-throughs

with the orchestra, Katherine Unha Keem, one of Angels'

two Korean prima donnas, commenced her race up the scale. When

she nailed the E-flat, both casts and the entire orchestra

stopped to applaud. Tonight, Jae Eun Shin has the part, and she

hits the note as well.

This scene has some Weiser fireworks to match Donizetti's. After

the performance of Lucia, Philip runs into Gino and a

couple of his drunken buddies. Gino greets him as a long-lost

brother, and insists they must celebrate. The four men end the

act with a thrilling quartet: The night is young/The stars are

bright/And there's magic in the air! It is the opera's most

joyous moment. For months of rehearsal, the singers and directors

had heard this section only in the Peabody opera studio with

piano accompaniment. Not until two weeks before the first

performance did they hear the quartet with a full orchestra. The

four men had been facing the orchestra so the players could hear

them, but for the climax they turned toward the rehearsal

audience, which was mostly other cast members and a few

observers. The crescendo built, the singers cut loose, the

orchestra resounded, and at the end everyone in the hall whooped

and applauded. Sirota turned on his podium, peered into the

audience until he found Weiser, and said: "Make a note--that

works."

Act 2, Scene 3

The next morning, Caroline sneaks off to Gino's house. She is

convinced that the Herritons don't really want the child, and she

intends to negotiate on her own for the baby. Gino is not home;

the housekeeper lets her in. Caroline sings an aria that explores

her complex feelings for Gino, then hides in the shadows when he

comes home. Not knowing she is there, he flings off his shirt,

which nearly hits her. Gino hears her startled yelp, leads her to

a chair, then announces that he is about to remarry. Caroline

erupts at the news, telling him he cannot ruin another woman as

he ruined Lilia. The moment echoes the first act, when Philip

unwittingly forbids the already consummated marriage to Lilia. It

is one of the structural unities Brunyate has smartly written

into his libretto.

Weeks before, rehearsal of this scene had dramatically

illuminated the character of Gino. Arturo Chacón, playing

the Italian, was rehearsing with Anne Jennifer Nash singing

Caroline. Brunyate was working out the blocking for the scene,

and Nash suggested that she cross in front of Chacón

toward a shrine Gino has kept in memory of Lilia. Brunyate didn't

like the idea, but he's open to suggestions and he let them try

it. Chacón and Nash ran the scene, and when she walked

past him, he suddenly grabbed her arm and violently whirled her

around. In a flash, Brunyate understood something about Gino he'd

never seen before: how his violence, which had not been scripted

to emerge until provoked in the third act, is ever present

beneath his surface amiability. His tenderness emerges only in

the aftermath of a violent act. In one improvisatory moment,

Chacón and Nash had revealed new depths to Gino's

character.

|

| Sirota conducts a

rehearsal. |

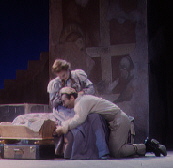

Late in the scene, Caroline and Gino bathe the infant, an

affecting moment that convinces Caroline she and the Herritons

must not take the baby from him. The audience cannot see the

conductor's face, but at an earlier rehearsal of this scene,

Sirota had turned from the podium with tears in his eyes, his

voice cracking with emotion as he said, "I have to get used to

that part. After all, I have to be able to conduct."

Act 3, Scene 1

A few days before the first curtain, Sirota had described

conducting Angels as "landing a 747...for two hours." The

orchestra players are young, many of them 18 or 19 years old.

"They're puppies," Sirota says. They received Weiser's score

about a month before performance, and Sirota patiently (now and

then impatiently, when they failed to concentrate) guided them

through its complexities, exacting the best from them with a

bluntness softened by humor. During one rehearsal the violins

kept botching a passage. Sirota stopped and asked them for the

key. They responded B-flat major. He pointed out that what they

kept flubbing was really no more than a B- flat scale. They all

knew how to play scales, and more important, they knew

that they knew how. With confidence inspired by Sirota's simple

explanation, they played the passage perfectly. Later, he stopped

them again, at another problem: "This is a mistake that the first

violins have made three times now. Make new mistakes."

Rehearsing the singers, he was always after more colors, a

greater range of expression. They were naturally resistant;

singers want to make beautiful music all the time. But Sirota

didn't want everything beautiful. "Boring," he told them. "You

sit there in the audience and say, 'Gee, that was pretty.' And

you get nothing else out of it. I will give you other

opportunities to tear up the scenery, I promise you."

The first scene of the final act takes place in a church, Santa

Deodata. It is a subtle and complex interlude in which Philip and

Caroline hesitantly work toward expressing the strong emotions

they're beginning to feel. For Philip, in particular, this is a

pivotal scene. He must express his awakening feelings for

Caroline and simultaneously convey that he doesn't quite know

what to make of the unexpected force of his emotions. The arousal

of passion collides with his English conventionality and

reserve.

From early on, Philip has been a sticking point for Brunyate and

Weiser. Their collaboration has been fruitful but not devoid of

tension. They could not agree on Philip. Says Weiser, "The more I

worked on the opera, the more I was rooting for Caroline and

Philip to get together, and I wanted the audience to root for

them, too. Roger feels very strongly that Philip is a latent

homosexual. That's a possibility, but I don't think that's what

the book is about."

After Weiser read Brunyate's first libretto, he wrote a long

letter detailing this and other differences, and the project

nearly fell apart. The gap seemed irreconcilable. Weiser went to

Brunyate's house, they had a long discussion, and decided to

persevere, working out their differences. The story had too

strong a grip for them to walk away.

But they still had to decide what to do with Philip as an

operatic character. He is rarely an active agent, always doing

someone else's bidding and just trying to flow with the current.

He begins the play as something of an arrogant twit, and though

he's much more likable and admirable by the end, he pales next to

the vital, passionate Gino. Throughout rehearsals, Brunyate and

Weiser still differed over Philip, as did the tenors playing

him.

Duane Moody's portrayal was always broader and more passionate

than that of his counterpart, Taylor Armstrong. Moody, who does

not lack self-confidence, was determined from the start to put

more life in Philip: "I picture Philip as a mama's boy but not a

weakling. The directors wanted to make him more feeble in the

beginning. I just can't see Philip as that passive."

Armstrong, a 23-year-old Pennsylvanian, consistently acted the

part with more English reserve, except for the church scene and

its aria, which begins with Philip claiming that he does not fall

in love but acknowledging how deeply Caroline has moved him.

Armstrong sang the aria in rehearsal as an expression of passion,

clasping Caroline's hand and gazing into her eyes.

Late on a Friday afternoon a few weeks before opening night,

Brunyate decided to rework the scene. He instructed Moody, who

was rehearsing while Armstrong watched, to not touch Caroline but

turn away and sing his lyrics as if he's beginning to sense what

stirs within him but cannot bring himself to address her

directly. Weiser's score for Philip's aria is music of love, and

Brunyate wanted Moody to play against that: Philip would sing his

denial of love, his body language would betray his confusion, and

the music would tell the audience of the passion he doesn't yet

understand.

Armstrong and Nash, watching Moody and Laurie Flint play the

scene, exchanged a look of concern tinged with frustration.

Armstrong protested that all along he had believed that Philip

knows he loves Caroline but simply can't tell her. This new

staging would change all of that, and thus dramatically change

his portrayal of the character. Brunyate heard him out, then let

him and Nash try various movements, finding their own way through

the scene.

Tonight on the stage, Armstrong does indeed turn away from Nash.

She silently approaches him as he sings the aria, and when he

turns back to her, he is startled by her closeness. But they do

not touch. When Caroline leaves the church, Armstrong hesitates,

then runs after her, only to return alone, disconsolate that she

is gone. The scene now conveys the awkwardness that Brunyate was

after, and the audience sees the acknowledgment of passion that

Armstrong had desired. It's the fruit of creative

collaboration.

Act 3, Scene 2

In the darkness of a rainy, miserable night, Philip stands by a

carriage awaiting his sister. Harriet suddenly appears, and it is

only after they have climbed into the carriage that he realizes

Harriet has stolen Gino's child. They race for the train station

and their carriage collides with another that bears Caroline. In

the aftermath, Caroline finds Philip, who has broken his arm, and

hears from the dazed Harriet that the baby was with them but now

is lost. Frantic, Caroline searches for the child in the

wreckage.

|

|

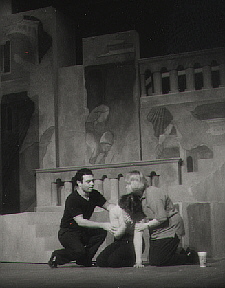

|

Gino erupts at the news of his

infant son's death (Moody, Brendan Cooke, and Laurie Flint, in

rehearsal). Then, spent, he collapses in sorrow (right).

|

Most of the singers in Angels are in their early or

mid-20s. Laurie Flint, one of the sopranos performing Caroline,

is not. She politely declines to state her age, but she is closer

to 40 than to 20 and has a 10-year-old daughter. Singing is her

second career. She had been working in hospital administration

when she had her child. Living in London at the time and coping

with post-partum depression, she began thinking about what she

would regret were her life to end suddenly. And she knew the

answer: She would regret never having pursued singing. She began

studying music again, and when Hopkins recruited her husband,

otolaryngologist Paul Flint, she set her sights on Peabody.

On stage, Caroline finds the baby amid the wreckage and realizes

that he is dead. She clutches the infant to her breast and

screams NOOOOO!!! with a depth of despair and anguish that sears

the audience. Flint had created this climax for the scene back in

January rehearsals. Watching her that day, one could understand

what emotional resources she might have drawn from to create such

a stunning moment. But how to account for young, childless

Jennifer Nash, who tonight plays the scene with the same profound

anguish? The explanation, for both sopranos, must be pure, raw

talent.

Act 3, Scene 3

Philip comes to Gino's house and reveals the awful truth of what

has happened. An enraged Gino wrestles him to the bed, torturing

him by wrenching his broken arm until Caroline rushes in and

halts the violence.

Arturo Chacón, a happy-go-lucky Costa Rican baritone,

stepped into the role of Gino as if it were a second skin. "Gino

is Latino in some ways," he explains, in accented English. "When

Gino say to Lilia, 'This is your home, with

me'...that is so Latino." Chacón has been a

favorite with his female castmates. In a 45-minute span during

one rehearsal, three of them found pretext to snuggle up and kiss

him. But it's frightening how menacing he can be when the part

demands it. When Caroline first pulls Gino off Philip, he whirls

around and violently tosses her onto the bed. During a rehearsal,

Nash, one of his closest friends in the cast, told him,

"Remember, Arturo, you are really strong."

For Brendan Cooke, a friendly Irish American who once wanted to

be a heavy-metal guitarist, Gino has not been the same sort of

easy role. He watches Chacón and says, "Gino comes

naturally to him. It's not natural to an Irish guy like me."

Chacón's every gesture says, This is my town, my house,

my woman. Cooke tends to move like what he is, a nice, gentle

man, and he struggled before getting a better grip on the role

days before the show opened. After weeks of listening to people

say, "Do it like Arturo's doing it," he finally got to hear,

"Arturo, why don't you try what Brendan's doing?"

Despite the difficulties--and a bout with pneumonia--Cooke

enjoyed the prominence of the role. "The baritone usually plays

the old drunk," he says. He also savored a bit of baritone's

revenge: "After we first rehearsed the scene where Gino torments

Philip, I called my old vocal teacher and said, 'I just spent two

hours smacking the crap out of the tenor. It was great.'"

|

Brunyate (pictured at right) wrote the opera's libretto,

based on E.M. Forster's

novel of the same title, and he is also the stage director.

Weiser composed the score. Their work on the project began seven

years ago, and they were still burnishing the show on the eve of

this first performance. The singers won their roles last

September and commenced months of study, vocal coaching, and

rehearsal. They got sick, got well, went to class, skipped class,

auditioned for summer jobs, pondered upcoming recitals, juggled

rehearsal schedules for other productions, learned staging,

learned revised staging, and practiced day after day after day.

For weeks, Angels has been the nexus of their young

lives.

Brunyate (pictured at right) wrote the opera's libretto,

based on E.M. Forster's

novel of the same title, and he is also the stage director.

Weiser composed the score. Their work on the project began seven

years ago, and they were still burnishing the show on the eve of

this first performance. The singers won their roles last

September and commenced months of study, vocal coaching, and

rehearsal. They got sick, got well, went to class, skipped class,

auditioned for summer jobs, pondered upcoming recitals, juggled

rehearsal schedules for other productions, learned staging,

learned revised staging, and practiced day after day after day.

For weeks, Angels has been the nexus of their young

lives.