|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Delayed & Denied

By Maria

Blackburn The eight chairs in the waiting room are filled, and the phones ring nonstop with calls from international students inquiring about taxes and work restrictions. In the middle of it all, foreign service assistant Susana Rodriguez tries desperately to fix the downed office e-mail so that she can read the 400 or so messages awaiting the attention of the four-person staff. "We had so many students in here yesterday they were hanging out the windows," says Nicholas Arrindell, director of International Student and Scholar Services. He's kidding. Sort of. The several hundred new international students on the Homewood campus each fall are required to check in so that the staff can notify the U.S. government that they have arrived at their destination on time. However, one day before their arrival deadline, 18 undergraduates and 32 graduate students have not shown up or even called the office. "Where are they?" Arrindell asks. "Nobody knows." Perhaps the missing students arrived in the country but have yet to reach Johns Hopkins, Arrindell says. Or maybe, the hassles that go along with gaining entry to the United States to study have led them to choose a school in another country — Canada, Europe, New Zealand, Australia. He's worried. "There are countries that are waiting for us to fall off our pedestal," Arrindell says. "No one wants to be made to feel like they are a terrorist when they are coming here as a student." Delays and denials for visas to travel to the United States aren't anything new. However, since the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, D.C., on September 11, 2001, security has gotten tougher, visa regulations have tightened, and many of Hopkins' 5,000 international students, scholars, faculty members, and researchers are finding that it's more difficult for them to reach their destination than ever before. Consider this:

|

||

|

There are no official figures detailing how many Hopkins

students, scholars, and faculty members from outside the

United States have been delayed by visa issues since

September 11. But anecdotal evidence abounds. Some

international students and scholars have had to wait a few

extra hours or a couple of days for interview appointments

with U.S. consular officials in their home country —

a new requirement that started last May. Many have been

left waiting for months because of additional security

checks. Others have been denied entry outright. "We've been telling people not to buy their plane tickets until after they get their visas because they won't know if they're actually able to come until then," says Arrindell, whose office serves students and some faculty from the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and the Whiting School of Engineering. At Johns Hopkins and at research universities across the country, many worry that the United States could be feeling the effects of these visa regulations for generations to come. "Every secretary of state since World War II has acknowledged that one of the greatest foreign policy benefits we've had going for us over the past 50 years is that the U.S. has been the nation of choice for those who want to get education outside their home country," says Victor Johnson, associate executive director of NAFSA: Association of International Educators. "Many leaders of the world have been educated in the United States, and they have come to know the United States, warts and all, not just a stereotype" of it, Johnson says. This knowledge gives leaders the advantage of being able to fully understand the United States when it comes to international relations, he says, and without it, the country will suffer: "If they aren't coming here, we won't have those relationships at the time we need them." The potential financial implications are tremendous. Although international students comprise only about 4 percent of all students at U.S. colleges, they contribute nearly $12 billion to the U.S. economy through their spending on tuition and living expenses, according to a study by the Institute of International Education. The Department of Commerce describes U.S. higher education as the country's fifth largest service sector export. At Hopkins, the majority of international undergraduates foot the bill for their entire tuition — without benefit of grants, loans, or other financial aid. At Hopkins' Peabody Conservatory, for example, where there are 200 international students, many pay the majority of their tuition. "Most international students don't qualify for need-based financial aid," says David Lane, Peabody's director of admissions. For colleges that are already seeing cuts in federal and state funding, the tuition dollars paid by international students are more important than ever, says NAFSA's Johnson. "Schools are being pinched all over the place and are having to cut back on academic programs," he says. "Foreign students who by and large pay full tuition are a lifeline for the schools and one they can ill-afford to lose due to short-sighted visa measures." The U.S. State Department doesn't release how many students have been delayed due to new visa regulations, according to spokeswoman Jo-Anne Prokopowicz. However, applications for all types of non-immigrant visas have fallen by 15 percent since September 11. In 2003, the State Department received about 541,000 applications for F-1 and J-1 visas, the most common type of student visas, a drop-off from 580,000 applications in 2000.

"We have made it abundantly clear — we want students

to come from overseas and learn," Prokopowicz says.

However, students and others need to realize that consular

officials are now following the regulations to the letter

as a matter of national security. "We have these laws in

place and we will follow them and we will protect

Americans," she says. "The process is serious. There is no

cutting corners." |

|

| Nicholas Arrindell, director of International Student and Scholar Services, assists Homewood's 1,000 international students and scholars. |

Until the world events of the last few years, it was not

uncommon for international students to miss visa renewal

deadlines or to show up at the last minute and still come

away successfully with that prized entry stamp to the

United States. Not so anymore.

Until the world events of the last few years, it was not

uncommon for international students to miss visa renewal

deadlines or to show up at the last minute and still come

away successfully with that prized entry stamp to the

United States. Not so anymore.Take the case of Hayder Mohamed Saeed, the postdoctoral fellow in civil engineering who is a native of Sudan, who thought he'd have no problem returning to his research in Baltimore after an emergency visit to see family in Italy last September. Saeed's J-1 visa had expired, but he assumed he could take care of the paperwork when he applied for a visa to re-enter the United States at the end of his 10-day trip. That was what he had always done in the past, he says. One year later, he's still waiting to hear whether his visa has been approved. Saeed, who suspects his nationality is causing the delay, had to give up his St. Paul Street apartment and has been staying with friends in Italy. No longer being paid by Hopkins for research he cannot do and unsure of whether he'll be allowed to return to his research fellowship, he is now looking for work in Italy. "I would have preferred that I would have been denied the visa instead of keeping me waiting for a year's time," says Saeed, who adds that his hope of returning has become dimmer with each passing week. He's sent e-mails to the U.S. Embassy in Rome, and has called and e-mailed Hopkins' international student office. The school's government relations office has asked U.S. Senator Barbara A. Mikulski's (D-Md.) office to intervene on Saeed's behalf, but he's received no word about his visa application. "I don't know if frustrated is enough to describe my situation, really," Saeed comments, in a telephone interview from Milan. "At the beginning I was frustrated. Now I am worried about my future. I have been totally ignored." Although all students undergo the same application process, their country of origin can influence whether they will be delayed, Hopkins administrators say. Because of concerns about terrorism, students like Saeed from places such as Sudan, Pakistan, and the Middle East face more scrutiny. Students and scholars also face delays if their field of study is on the U.S. State Department's security alert list and is considered to have a "dual use," says Enrico Dinges, assistant director of public and international relations in the School of Medicine's Office of International Student, Faculty, and Staff Services. Fields on this list include ones with an obvious potential for terrorism, such as nuclear weapons development, as well as more innocuous seeming subjects such as architecture and biology.

Su Gao, a PhD candidate in

biological

chemistry at the

School of Medicine, experienced an unnerving visa delay

last March after he went home for what was to have been a

three-week visit with his parents in Beijing, China. The

29-year-old had been spending long hours in the lab

researching a new anti-obesity drug and was feeling

homesick. "My parents are everything to me," he says. So,

after submitting a paper for publication in Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences, he flew home. "I thought

it was a terrific time for me to take vacation, refresh

myself, and then go back to work," Gao says. |

|

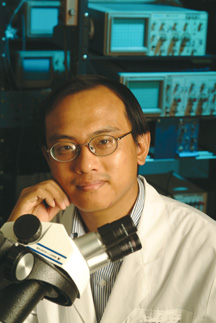

| "I could have lost my scholarship," says Su Gao, a PhD candidate in biological chemistry at the School of Medicine. "I would have lost my chance to study in America." |

The day after he arrived in Beijing, Gao went to the U.S.

Consulate to apply for a visa to return to the United

States. "I wasn't nervous at all," he recalls. On previous

visits, the required interview with a U.S. consular

official had gone quickly. "They saw my application,

understood [that I was a student], and let me go," he

says. This time, two days after his interview, Gao was told his visa application had been sent to the State Department in Washington, D.C. With no visa and no way to return to Baltimore, he called his advisor at Hopkins to let him know he had been delayed indefinitely. Since Gao had no official correspondence from the State Department, he could only wonder why he had been detained. He sent monthly e-mails to his advisor, M. Daniel Lane, and to the department chair, asking them to contact the State Department on his behalf. Lane made contact but was unsuccessful. "You could get no feedback," says Lane. Frustrated, Lane asked the office of U.S. Congressman Elijah E. Cummings (D-Baltimore) to see if they could find out from the State Department why Gao's visa was taking so long. "They said his name was listed but no action had been taken," says Lane, who learned that Gao's application had been sent to Washington, D.C., for an additional security check, a measure taken for applicants in fields deemed sensitive by the U.S. government. For weeks the story stayed the same. Meanwhile, the three other researchers on Gao's team proceeded with their work on the anti-obesity drug. At home in China, Gao worried about getting dropped from the project and the program. "I could have lost my scholarship," he says. "I would have lost my chance to study in America." Finally in mid-July, four months after leaving Baltimore, Gao was told to return to the embassy in Beijing for a second interview. There he was notified he had received his visa and could return to Hopkins. Once he was safely back in Baltimore, Gao couldn't forget what had happened. Using electronic bulletin boards, he sought out other Chinese students nationwide who had also experienced delays returning to the United States. He found 400 people with similar stories. The students have joined together and have been sending letters to Congress, the State Department, and others to notify them of how foreign students studying in the United States are being delayed. "We have to have our own voice," says Gao. "The entire purpose of doing this is to try to let people know our situation and the importance of letting us go back [to our schools] on time."

Remembering the research he was forced to leave behind for

several months, Gao has advice for other international

students who are considering going home for a visit: "Don't

go back until you get your degree or are 100 percent sure

you can return," he warns. |

|

| Janice Shannon, Peabody's international student advisor, says that keeping up with paperwork is keeping her away from her students. |

For the university offices that deal with international

students, new rules and regulations are also driving some

delays — and boosting staff workloads.

For the university offices that deal with international

students, new rules and regulations are also driving some

delays — and boosting staff workloads. Currently, all foreign students must be entered into the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS), a newly created national database that tracks the whereabouts of foreign students and exchange visitors during their stay in the United States. Prior to SEVIS, schools were required to maintain information about students at their institutions, but the decentralized, paper-driven system was flawed and inefficient, says Garrison Courtney, spokesman for the U.S. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement. "For the last 40 years the same information was being sent to us on paper by schools, and it was a really inefficient, slow way of doing things," he says. The system was so full of loopholes that people could apply for and receive visas by saying they were planning to study in the United States but never actually show up for classes. The U.S. State Department and U.S. Border Patrol inspectors are supposed to enter information into the SEVIS system that is confirmed when students arrive at their designated schools. SEVIS' benefit is that it allows for real-time access to information, compared to the six months to three years it used to take for student visa applications to be processed. "Now we can identify a lot quicker if a college student fails to show up for class," Courtney says. But the necessary information about students isn't always in the SEVIS database when it's supposed to be, Hopkins administrators say, thereby causing delays and additional paperwork. And keeping up with SEVIS is taking away from the time advisors spend counseling students, says Janice Shannon, Peabody's sole international student advisor. She's the person the conservatory's international students seek out when they want to know where to go after graduation, have problems at home, or need help working through issues with other offices at the university. "Students come to us with everything," she says. "I'm the front line." Tracking students for SEVIS is occupying so much of her time, she says, that she has to devote one afternoon a week to catching up on paperwork, instead of advising students. "I'm an international student advisor; I'm not working for the government," says Shannon, who also teaches English as a Second Language. "I have to close my door [to students] now one afternoon a week. I've never had to do that before." At Hopkins' Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, where at least 36 percent of the 540 full-time students are from outside the United States, the amount of paperwork involved with processing foreign students has grown so much that the school hired its first full-time international student advisor in September. Previously, international student advising was done through the Registrar's Office.

"It's become necessary for everyone to focus on this issue

even more than we did before," says Bonnie Wilson,

associate dean for student affairs at SAIS. "Because there

are so many rules and regulations and because they change

frequently, students themselves want to be sure what

they're doing is correct. There's more anxiety, more desire

to get one-on-one counseling, more students waiting in line

in front of the Registrar's Office." |

|

| Su Gao and other Chinese students studying in the U.S. have been writing letters to Congress and the State Department to raise awareness about their visa troubles. |

This year the Department of Biostatistics at Hopkins'

Bloomberg School of Public Health received 224 applications

for eight funded positions. "Biostatistics involves

mathematical science and health science," department chair

Scott Zeger explains. "You need to find students with a

high degree of mathematical aptitude, plus an interest in

human health."

This year the Department of Biostatistics at Hopkins'

Bloomberg School of Public Health received 224 applications

for eight funded positions. "Biostatistics involves

mathematical science and health science," department chair

Scott Zeger explains. "You need to find students with a

high degree of mathematical aptitude, plus an interest in

human health."Three of the positions were offered to, and accepted by, students from Beijing University's Department of Mathematical Sciences, applicants Zeger terms "three of the very top students in the world." But the Chinese students aren't coming to Johns Hopkins this fall. Earlier this summer, their visas were denied. "This seems to have nothing to do with national security," says Zeger, adding that of the 15 Chinese students from his program who applied for visas in previous years, none were denied. "These are three young outstanding Chinese students who want to study here." Under the terms of most student visas, students must return to their home countries after their course of study has been completed. Because China has such a large number of people who leave to study and don't return, officials there have long been extremely sensitive about granting visas to people who want to study in the United States, according to Medicine's Enrico Dinges. This scrutiny has increased significantly in the last two years, administrators say. Consular officials in China "really scrutinize students' ties to their home country," he says. They want to know whether a student has family there, whether the student owns property, or has a job to return to. "If you are able to leave and you don't have any ties to your home country, then you are more able to come to the United States and establish a life here," Dinges says. Zeger and others believe that such intense scrutiny is jeopardizing medical research. Graduate students in biostatistics conduct National Institutes of Health-funded research on AIDS, SARS, bioterrorism, chronic disease, air pollution, and mortality. "These students are essential to our research programs reaching full potential," Zeger says. "It hurts our department because we lose a couple of good students. It hurts American science because there's already a shortage of biostatisticians, and now there will be fewer trained biostatisticians, and the shortage will persist. "I think the visa counselors in China and elsewhere are following a change in American policy ... and it's a change that's extremely detrimental to Johns Hopkins," he says. "We need to educate the State Department to prevent this sort of disruption of a pipeline of very important scientists for worldwide medical research." Nationally, foreign-born scientists and engineers make up 26 percent of science and engineering doctoral degree holders, according to the National Science Foundation. Nearly half of graduate students in engineering and computer science and almost one-third of mathematics students were born outside the United States.

Science isn't the only casualty.

Paula Burger, vice provost

for academic affairs who serves as vice dean for

undergraduate education in the Krieger School of Arts and

Sciences, says international students, scholars,

researchers, and staff are "absolutely vital" to Johns

Hopkins as a university. "We depend on them not only for

the excellent source they are of graduate students but also

of undergraduate students," she says. "They not only

support research labs that depend on them but also add

significantly to the diversity and richness of campus

life." |

|

|

In the midst of all the stress and frustration at Hopkins

surrounding visa delays, there are success stories. Last

spring, Hopkins' Jef Boeke began recruiting Yale University

molecular biologist Heng Zhu for a faculty position at

Hopkins' new High Throughput Biology Center. Zhu, an innovator in the new field of proteomics, wanted to come to Hopkins but stopped short of accepting the position until his fiancˇe, Annie Gao (no relation to Su Gao), could see Baltimore for herself. Gao lived in Beijing and had never been to the United States before. When Gao's visa application was denied and it looked like Zhu might not take the job because of it, Boeke got creative. He assembled a care package of coffee table books about Baltimore, Hopkins course catalogs, and a Blue Jays T-shirt and baseball hat, then enlisted Min Li, an associate professor of neuroscience and associate director of the High Throughput Biology Center, to deliver it all to Gao in person in Shanghai. Their sales job worked: Gao liked what she learned about Baltimore and Johns Hopkins. In August, Zhu agreed to accept the position at Hopkins. His plan is to return to China, marry Gao (thereby overcoming the visa obstacle), and bring her back to the United States. He hopes to start work here this fall. Boeke is pleased that Zhu — a scientist he calls "one-of-a-kind" — accepted the job. But he's concerned that other international scientists may be prevented from coming to the United States in the future. "The typical lab in basic sciences is at least 25 percent Asian, and in many cases it's a much higher percentage than that," Boeke says. "This issue is very critical for a place like Hopkins. This is very competitive research. An unexpected six-month delay can affect the entire institution. We want to have the best people as our colleagues. That's the bottom line." Maria Blackburn is a senior writer for Johns Hopkins Magazine. |

|

|

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street |

The Johns Hopkins Magazine | The Johns Hopkins University |

3003 North Charles Street | Suite 100 | Baltimore, Maryland 21218 | Phone 410.516.7645 | Fax 410.516.5251 |

|